Looking back at Ghost in the Shell

Memories from an internship at the company that brought it to America

A rogue algorithm delivering fake news directly into the brain-stems of citizens, driving them to terrorist acts?! No, I’m not talking about the January 6th insurrection or generative AI. This is the plot, in broad strokes, of Ghost in the Shell, a Japanese animated feature from 1995 that blew the minds of American arthouse moviegoers. I was one of them. It was one of several anime that convinced me I wanted to work with Japanese fantasies for a living, stoking my dreams of becoming a translator or, eight million kami willing, a producer or creator of some kind myself.

I bring this up because there’s an interesting article about the history of the film’s production on the Animation Obsessive newsletter. I spent a summer interning at Manga Entertainment, the company that helped fund the movie, in 1996. The article stirred memories, and got me thinking about how much has changed since the film first came out, almost three decades ago (sigh).

Back then, anime-in-translation represented a niche industry at best. Today it is one of the most vibrant entertainment fields on the planet, with more Gen Z’ers surveyed claiming to watch anime than football. Back then, anime importers chased elusive one-off hits. Today, the game is all about streaming a huge number of series, the more episodes the better. And most of all, Nineties-era companies craved legitimacy, the better to expand anime’s audience from the fringes into society at large. Ghost in the Shell was one of the most successful of these early cross-over hits.

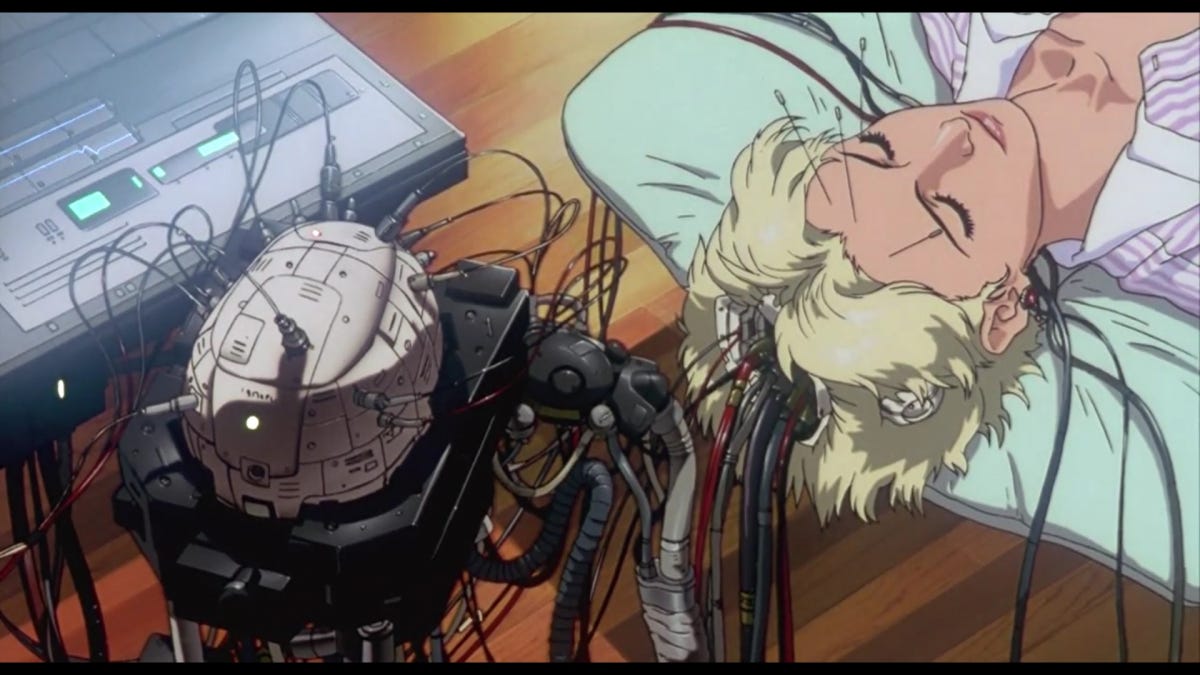

It was a cyberpunk thriller, adapted by director Mamoru Oshii from a manga by Masamune Shirow. The title comes from the protagonist’s predicament. She is a commando who has over the years replaced nearly every part of her body with higher-performing artificial parts. (We know this because, in classic Nineties anime fashion, she spends much of her time without clothing.) With little of her original self left save her consciousness, she wonders what makes her human — a paradox thrown into sharp focus by the antagonist, a sentient AI that wants to experience life in a human body. The story, set in what then felt like a very far-off 2029, was smart. The art was stylish. And the soundtrack was arguably even better, composer Kenji Kawai’s traditional instruments and chants providing a haunting counterpoint to the high-tech imagery onscreen.

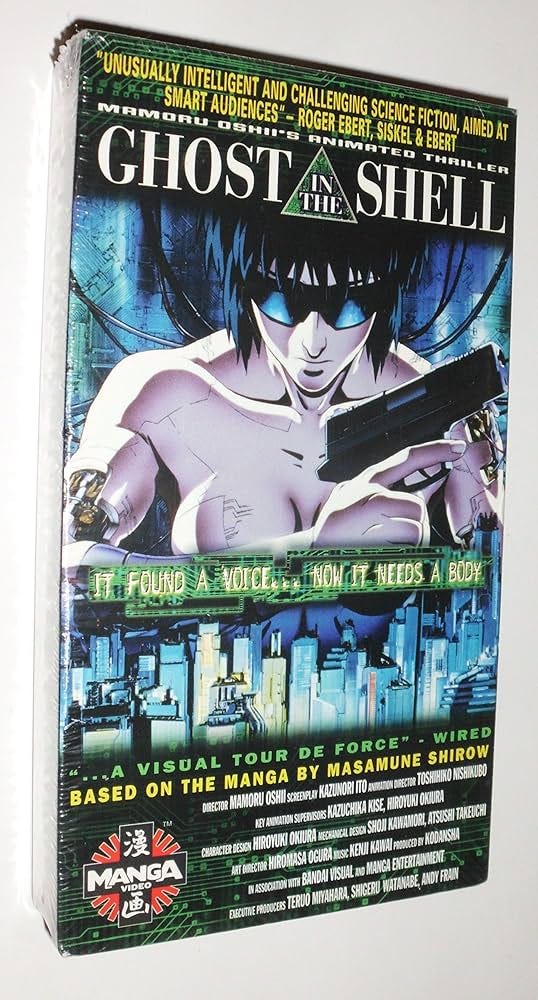

Ghost in the Shell was an early example of something that’s become the norm today, an international anime co-production. Manga Entertainment helped underwrite the film. The bet paid off: Ghost in the Shell earned $500,000 ($1 million in adjusted dollars) from a very limited arthouse run. Then it emerged as a phenomenon on home video, selling hundreds of thousands of tapes. In the summer of 1996, it hit #1 on the Billboard Top Video Sales chart, outselling Hollywood hits like Jumanji and Pulp Fiction.

I know this well, because I was there. I interned for several months at Manga Entertainment’s Chicago office in 1996, when the company was flying high on the unprecedented success of ushering an anime film into the American zeitgeist. The company was in a block of townhouses that had been refurbished into work space on North Hudson Avenue, and had that hip startup vibe, with all the exposed brick walls and ductwork on the ceiling and all of that. I’d drive up from Blue Island every morning, where I was staying with family, and think: this is it. I’m finally in The Industry.

Like any intern, the majority of my tasks were of the “gofer” or secretarial variety, answering phones, stuffing envelopes, packing boxes of promotional products. But another, more fun part of my time was spent screening stacks of tapes and writing up reports in hopes of identifying the Next Big Thing. This video “slush pile” was where I first saw Golden Boy, B’t X, and a slew of other mid-Nineties (and mid Nineties) fare. Manga Entertainment was, at the time, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the British music titan Island Records, and they wanted hits, hits, hits. I wasn’t privy to the byzantine multinational financial arrangements that kept us afloat, but I could hear the muffled calls from behind closed office doors, sense the tension quietly growing as the company struggled to reel in another cybernetic whale like Ghost in the Shell.

The internship petered out after a few months, with no full-time job forthcoming. I was crushed – so much for my big shot in The Industry! But we parted on good terms. Some time after, the company even gave me my first professional job as a translator, working on promotional materials for the film Tetsuo 2: Body Hammer. It was probably for the best that I didn’t land a position there. Times were changing for anime importers. What had started as a cottage industry run by a handful of early-adopter fan-weirdos (a term I use as a superlative) was rapidly being subsumed by corporate competitors. Island was one, but their music-industry knowhow was no match for natives with long experience in anime, like Pioneer and Bandai Visual. Manga Entertainment shuttered its Chicago offices in 2006 without ever landing, let alone funding, another crossover hit. A series of cable and film companies inside and outside of the US have been swapping its assets among themselves ever since.

Looking back, it’s obvious I was witnessing a paradigm shift in the way anime was prepared for and consumed by foreign audiences. Today, in the streaming era, series are the dominant format. The longer the better. But that wasn’t the case in the Nineties. It was very hard for anime companies to make money off of a series, because they had to be released on individual videotapes. I recall several of my suggestions for acquisitions being shot down because of how steeply sales dropped off, no matter how well the first volumes sold. This is why Manga Entertainment hungered for standout, standalone features. But even that was a gamble. For all the time and money the company invested into Ghost in the Shell, it turned out to be wildly out-earned by a much cheaper acquisition: Ninja Scroll, an outrageously ultraviolent and misogynistic period piece brimming with sadistic sex and gore. It filled the coffers but did very little to bestow that much-wanted legitimacy on the company or the medium as a whole.

This highlights another big change that was brewing around this time. For most of the Eighties and Nineties, the traditional demographic for imported anime consisted almost entirely of young men. It’s no coincidence that someone like me wound up on Manga Entertainment’s doorstep looking for a job. The company catered to men near-exclusively, with edgy mascots and slogans that made even me roll my eyes. It’s particularly cringe-y, looking back, because women always played major roles in the nascent anime fan scene. But the industry wouldn’t really embrace them until the surprise success of Sailor Moon in 1998.

Toonami, the late-night cable television block that hosted Sailor Moon, took note and began pivoting heavily into Japanese content; it was there, and not movie theaters or videocassettes, that large numbers of viewers first began to cultivate a taste for Japanese fantasies such as Dragon Ball Z and (later) Gundam Wing, Tenchi Muyo, and Cardcaptors. Then came a massive hit out of nowhere that changed everything.

Pokémon the cartoon series debuted on American television in September of 1998, just days before the arrival in stores of the Game Boy cartridges Pokémon Red and Blue. It would soon be followed by the Pokémon Trading Card Game. This trifecta swept schoolyards across the US, then the rest of the world. By 1999, it was a full-blown, planet-wide fad. Time wrung its hands about “Pokémania,” which they dubbed “a pestilential Ponzi scheme.” A scheme it may have been, but the cartoon’s success – along with Digimon and other rivals – fast-tracked an entirely new, young, and more gender-balanced audience into anime.

This also happened to overlap with a time when Western societies were increasingly coming to resemble post-Bubble Japan, with declining birth rates, profound economic disruption, and high levels of unemployment. Perhaps this is another reason why Millennials, who were literally raised on Japanese fantasies like anime, manga, and video games, became some of the medium’s most ardent supporters in the decades to come. Gen Z has taken this (Dragon?) ball and sprinted with it, making anime one of the most sought-after forms of content in the streaming industry.

There are still anime auteurs out there, of course, the Shinkais and Miyazakis and Hosodas, just to name a few. But again, gambling on an auteur is a risky business. Oshii never directed another film that came even remotely close to matching the financial success of Ghost in the Shell. His sequel flopped, and the later 2017 live action version — well, the less said about that the better. The future didn’t lay in searching for the Next Big Thing. It was all about building platforms, cultivating deep catalogs that could be streamed in an infinite scroll of endless content. Today, it isn’t big-budget movies but franchises that win hearts and minds: long-running series that encourage immersion and participation, the sorts of things that can be lived as a lifestyle, rather than simply experienced, as is the case with a film.

I never did manage to land another job in the anime industry, for better or for worse. I made my living localizing video games and manga instead. But no regrets. We live in a world that’s starting to look a lot like Ghost in the Shell, but the irony is that anime doesn’t look much like it anymore. And that isn’t a bad thing. Like the human Ship of Theseus that was that film’s protagonist, the import anime industry has been slowly rebuilt over the decades, making it a much more inclusive form of entertainment for all sorts of people, all over the world.

The only place to rent anime VHS in Toronto in the 90s was Suspect Video, which specialized in hardcore pornography. Anime and porno. That says it all about anime's cultural cache in those days.

Very interesting! I was born in 91 and definitely one of those kids sucked into the pokemon franchise. But I have much earlier memories of coming across anime on television. I know I was watching Sailor Moon as early as age 4 or 5 on public TV in the US, that was before Toonami took it. I think I must have also come across children's anime in some other way, because I have a vague but distinct feeling of nostalgia for shows made in the style of azuki-chan.