“Hoarder Hygge” is the Anti-Zen

Sorry, KonMari fans: Japan’s most charming spaces are its least tidy

Westerners have long associated Japan with immaculately curated minimalist design – an aesthetic often referred to in English by the confusing loanword of “Zen.” I say confusing because this Westernized appropriation of the term causes utter bewilderment in Japan. In Japan, Zen isn’t a style; it’s a religious order. Mentioning “Zen” there is more likely to conjure up images of a Buddhist monk whacking a meditation-sitter with a bamboo stick than it is, say, an iPhone. The idea of Japan as an immaculate minimalist utopia persists today, as seen in the global success of a fantasy-delivery device in the form of a book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing.

As anyone who has spent time living in Japan knows, that magic certainly doesn’t seem to have changed life here. Public spaces can quickly devolve into dumping grounds. Gomi-yashiki (“trash homes”) can be found in many neighborhoods. And even the dwellings of those who aren’t beset by the hoarding impulse can feel positively crammed with their owners' possessions.

Perhaps this is because the opening of private spaces to outsiders, in the form of house-parties or even get-togethers, isn’t really something most people do here. In cities, coffee shops and karaoke boxes and izakaya and love hotels serve that function instead, catering to everything from business meetings to intimate encounters. This “outsourcing” of social interaction could be due to the reduced floorspace of urban dwellings. Or it could be because, insofar as I’ve been able to determine in twenty years of living here, people don’t seem to status-signal with their living quarters, as homeowners do in the West.

Signaling via one’s possessions is a different story, of course. The “Three Divine Treasures” of a television, refrigerator, and a washing machine representing the must-have status symbols of the Sixties, for instance. This intersection of private space and personal stuff is where things get interesting. Japan may or may not possess the magic of tidying up, but its untidy spaces can be magical in their own rights. In fact, I think they’re where the most fun happens, where the best things get made.

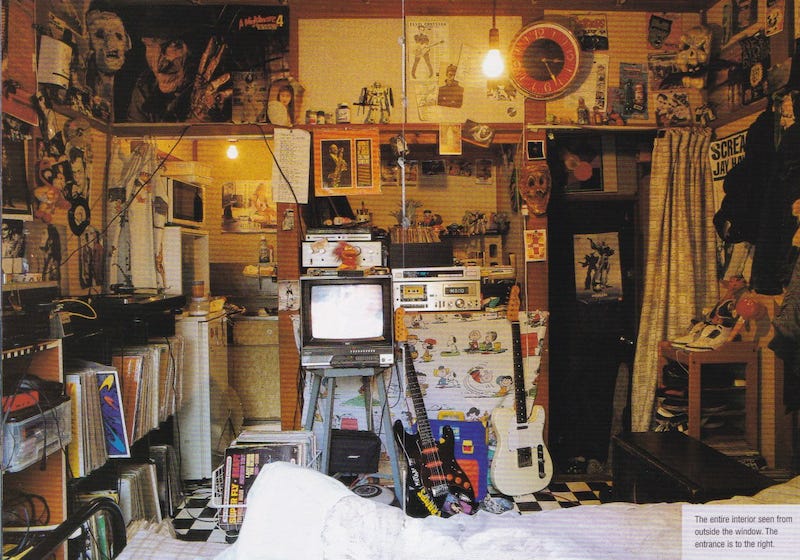

The photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki is perhaps Japan’s most famed chronicler of Japan’s cluttered side. His 1993 book Tokyo: a Certain Style, which showcased the homes of urban dwellers in their naturally untidy states, was the first to really celebrate this largely unseen side of daily life. Translated into English by Alfred Birnbaum several years later, it skewered the Western obsession with idealized Japanese aesthetics, which Tsuzuki dismissed as “some Japanophile’s dream.” He continued, “to a European or American, a good many of the rooms must look like something out of the slums. But you should see some of the stuff we keep in those dumps. Real expensive luxury items.”

He dubbed this nesting instinct “the cockpit effect,” but I prefer thinking of these places as having what I’m going to call a certain hoarder hygge. And in fact super-cluttered, borderline out of control spaces are some of my favorite in all of Japan. Cramped izakaya, shops jammed with precarious towers of books or toys or even Buddhist altars, the spaces where creatives work, the rooms where collectors nest amid a lifetime of treasures. They’re hypercozy, and I love them.

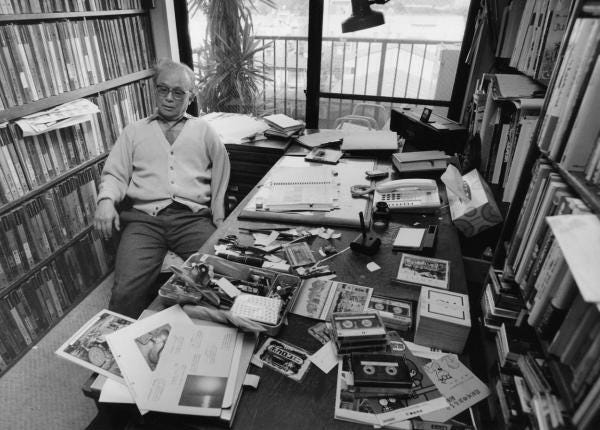

Japan’s love-hate relationship with clutter arguably dates back centuries (more on that in a moment). But in a more recent pop-cultural sense, the late Nagisa Tatsumi fired the first salvo in the Tidying War with a 2000 book called Suteru! Gijtsu (“The Technique of Just Throwing Things Away”). Her straightforwardly-named success paved the way for more esoteric takes, such as Hideko Yamashita’s Shin Katazukeho Danshari (“A New Cleaning Method: Danshari”), which rocketed up Japanese bestseller charts in 2009. Written with kanji-characters for “refusal,” “separation,” and “disposal,” danshari injected a dose of Buddhist philosophy into the clean-o-sphere. It swept Japanese society to such a degree that the word was actually nominated as 2010’s buzzword of the year. It lost out, somewhat amazingly, to the phrase Ge Ge Ge, from a hugely popular biopic about yokai-master Mizuki Shigeru called Ge Ge Ge no Nyobo (“The Ge Ge Ge Wife”). Come to think of it, Mizuki is another guy with a real sense of hoarder hygge. Those shelves packed with references! The desk covered with field recordings!

When Marie Kondo’s book arrived in the States in 2014, her Shinto-inflected take on tidying felt like a bolt out of the blue to American readers. But in fact it was simply the natural progression of a fad that had been playing out in Japan over the previous decade. Released in its home country in 2010, the book (or more precisely, method) sold very well there. But the boom faded out a few years later, as most self-help fads do in Japan, or anywhere else. The big difference among Tatsumi, Yamashita, and Kondo is that the latter managed to find a second life abroad, and a much bigger one at that. It helped that Kondo found a talented translator, who rendered the quotidian word tokimeki as “spark joy,” transforming an unremarkable Japanese term into a magical-sounding English catchphrase.

It also helped that her book slotted neatly into that centuries-old Western image of Japan as a paragon of spiritual and physical cleanliness. As my wife and longtime creative partner Hiroko wrote in The New Yorker a few years back, foreigners have been marveling at the cleanliness of Japanese citizens and streets since the 1850s. These are good impressions! But they’re also superficial. None of these visitors from foreign lands were spending much time inside average folks’ homes. Behind the scenes, things inevitably get messy. This is why Osoji (“Big Cleanings”) of the sort Hiroko wrote about became a thing in the first place. Those ancient annual cleaning rituals are the spiritual precursors to every tidying method to follow.

In the West, Japanese cleaning magic is so omnipresent as to have spawned the verb “Kondo-ing,” and “sparking joy” returns close to 75 million results on Google. (Tokimeki gets less than half that, just to show you how much less cachet it has here.) In Japan, the KonMari boom has long since faded, because her system lacks even a whiff of the exoticism it has abroad. She was simply the last tidier standing, after a decade-long battle royale I like to imagine was fought with brooms and dustpans and Hefty bags. But I also think it faded because Japanese understand that while tidy is nice, there’s also a certain chic in a densely-packed, nest-like space, controlled chaos that beckons you in.

Kondo was the one who most effectively translated the culture of the Big Cleaning into words that resonated with foreign readers. I wonder who will be the first to really convey the glory of Japan’s hoarder hygge to the masses. Perhaps it is simply something one has to experience themselves, by immersion. In the meantime, ask yourself this. If Japan really were a paragon of tidiness, why would it need to anoint a Marie Kondo in the first place?

That kokeshi doll workspace looks like everyone's office at M1GO.

Jeez, it's so refreshing to read this! I'm glad you properly gave a name to this phenomenon, because it's an uncredited factor in the charm of Japanese daily life. Sure, places can be small and cramped, but that can also have an appealing intimacy. In the commercial context, I'm thinking of the cozy neighborhood izakaya where you get to know your neighbors, or the microscopic stationery store that somehow has everything you need tucked into tiny corners. Perhaps it's less known outside of Japan because it's less replicable, at least in places with a "bigger is better" mindset.