Halloween Special: the Yokai Guy

Manga master Shigeru Mizuki breathed new life into the undead

In 2013, I was hired to write the forward to an English-language collection of stories from Shigeru Mizuki’s Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro manga series. That book is now out of print, so I’m making an updated version of that essay available for everyone to read. Mizuki passed away in 2015 at the age of 93. English editions of Mizuki’s work are available from Drawn and Quarterly.

Shigeru Mizuki’s Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro is quite possibly the single most famous Japanese manga series you’ve never heard of, even if you happen to be a manga fan. Which is a shame, because Kitaro’s uncanny pulse beats beneath the surface of Japanese pop culture like a tell-tale heart.

Kitaro is heir to a vast cultural tradition that is intimately familiar to Japanese, and all but unknown in the West: the yokai, mythological shape-shifters and monsters that have populated Japanese folktales since time immemorial. They are the things that go bump in Japan’s night.

A strict definition of yokai is maddeningly difficult to pin down. Over the years many translations have been floated: “monster,” “ghost,” “demon,” “goblin” and more, but none of these quite cut it, as they’re saddled with their own Western cultural baggage. Yokai are yokai – just like sashimi is sashimi, not “cold raw fish.”

Legend says the islands of Japan are home to some eight million gods, known as kami. These multitudes aren’t like the monolithic Capital-G-God of Judeo-Christian tradition. Some kami are benevolent creators and protectors; others are angry, in need of appeasement. There is no real hierarchy among them, but there are greater and lesser, stronger and weaker; there’s even, as a 2010 J-pop song goes, a God of the Toilet.

The yokai fall somewhere along this vast continuum. Unlike hallowed gods of the heavens, they actually inhabit our physical world. Yet they aren’t precisely of it. Some yokai are humanoid or animal-like. Others are the faces behind inexplicable natural phenomena, superstitions personified. More than a few are what we might call “haunted” objects, everyday tools or things taken uncanny sentient form. Some are dangerous, some indifferent, some simply mischievous, a few even benevolent. But to a one, they’re inherently unpredictable, utterly beyond human control, and thus deserving of respect.

Mizuki wasn’t the first artist to attempt drawing the appearances of the various yokai. But he is one the best known and indisputably the most popular. If you ask the average Japanese to describe a yokai, chances are one of Mizuki’s portrayals will spring to mind. And the reason why is simple: Kitaro.

Kitaro is the glue that holds a nation’s worth of disassociated folk characters together. Being based in the oral tradition, yokai tales are a mix-and-match patchwork of local legends from across Japan. Mizuki’s genius was to weave these unconnected stories together into a single narrative, transforming the terrors of the night into a force for justice. Without Kitaro, we’d be adrift in the world of the yokai.

Mizuki’s work is distinguished by a deep and abiding love for folklore. He was weaned on folktales in his youth in the countryside, and continued to collect and study them throughout his life (in addition to his manga, Mizuki has also published numerous illustrated encyclopedias of folk beliefs regional and global.) Mizuki’s success was due in no small part to his knowledge of and affection for three key artists that preceded him: Sekien Toriyama, Lafcadio Hearn, and Kunio Yanagita.

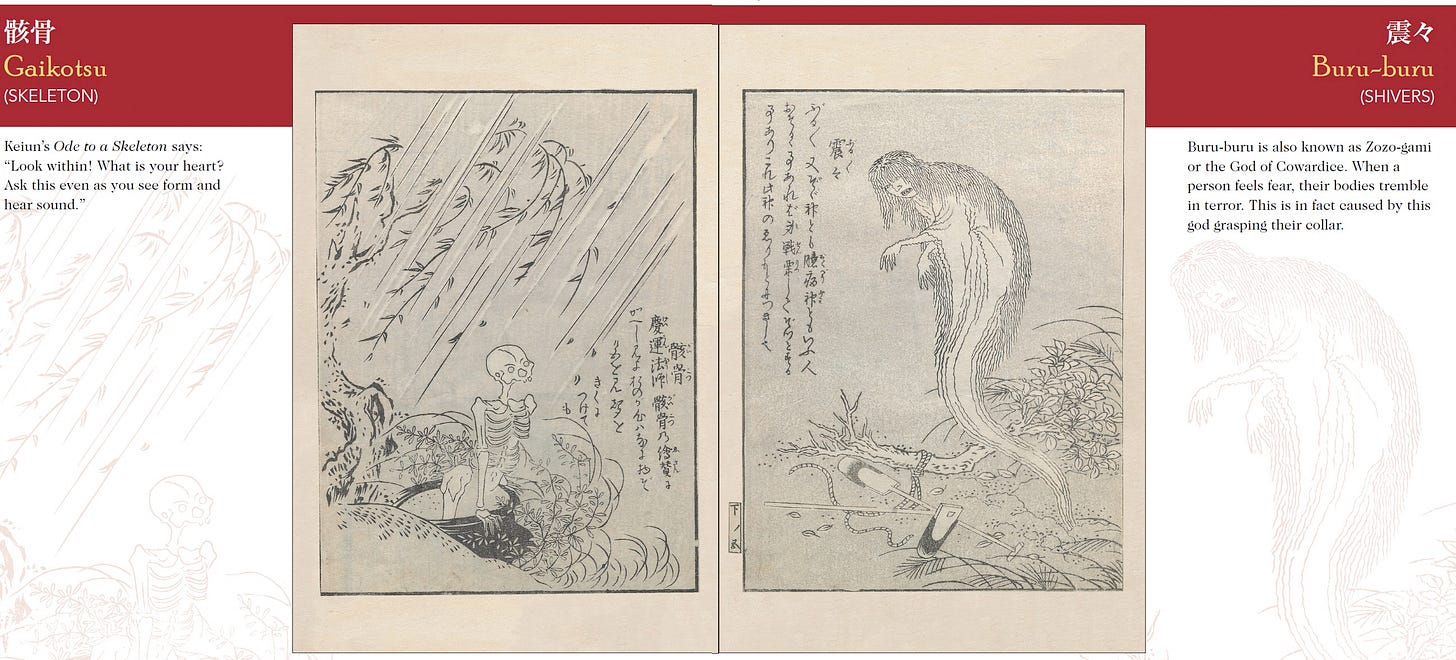

Although it seems the yokai have always haunted Japan, their first heyday came at the turn of the 19th century thanks to the artist Sekien Toriyama. In 1776, he published the world’s first visual guide to the yokai, called Gazu Hyakki Yagyo (which Hiroko Yoda and I translated into English as Japandemonium Illustrated in 2016). Sekien’s work was more than just the first catalog of monsters from folklore; it represented the first time many of them had ever been illustrated at all. His tongue-in-cheek approach interwove traditional descriptions with social satire, and proved so popular that it spawned three sequels. This makes his series one of the proto-blockbusters of early Japanese pop culture – and a direct forerunner of modern manga.

A little over a century later in 1868, Japanese ports opened to the world, ending two hundred years of isolation and ushering in a wave of foreign interest that came to be called “Japonisme.” Japanese porcelains, scroll paintings, and woodblock prints inspired the likes of Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Degas, and Whistler; Van Gogh even took a stab at copying a Hiroshige print with a brush and oils. Art paved the way for literature. At the turn of the 20th century, a journalist by the name of Lafcadio Hearn, together with his wife and interpreter Setsuko Koizumi, collected and translated superstitions, ghost stories, and folktales from all over Japan. His English adaptations represented the first time many of these stories had ever been committed to paper in any language. After Hearn’s death in 1905, his books were translated into Japanese, sparking a renewed interest in tales of the macabre among locals.

Among them was a government bureaucrat turned writer, Kunio Yanagita, who began compiling folktales of his own during business trips to far-flung Japanese locales. His 1910 The Legends of Tono, which described the supernatural legends of the isolated northern village of the same name, proved a surprise hit and almost single-handedly established the academic field of minzoku-gaku, folklore studies, in Japan.

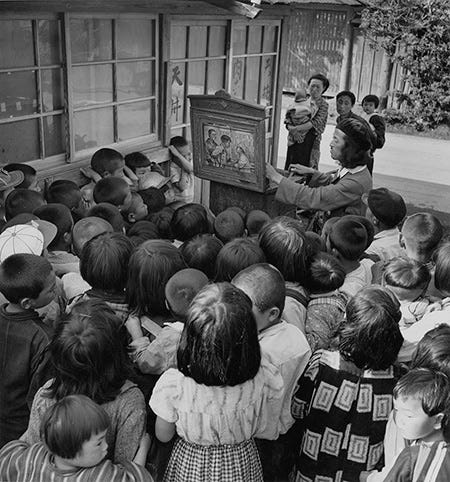

Which brings us to Shigeru Mizuki. Born in rural Tottori prefecture in 1922, he was conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army in 1942. They sent him to the island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea, where he lost his left arm in combat. After war’s end he returned to Japan and found employment as an illustrator for kashi-hon (rental comics) and kami-shibai – narrated “paper dramas” performed by traveling peddlers. In spite of the great enjoyment this entertainment brought children in that impoverished postwar era, it was a brutal industry for the artists who actually created the content. Mizuki spent many years struggling to feed his family on his meager earnings, when he even got paid at all.

In 1954, Mizuki’s publisher tasked him with reviving a once-popular kami-shibai series called Hakaba no Kitaro, or “Graveyard Kitaro,” created by artist Masami Ito and writer Tajimi Kei. Mizuki took the series in new directions with a series of short stories for the rental-comic market, but struggled to find an audience for the character.

However, major change was afoot. By the late Fifties, rental comics and kami-shibai publishers found themselves squeezed out of business by a new form of entertainment: manga. These thick compilations of comic serials were sold on newsstands every single week – and unlike their haphazardly managed predecessors, they promised a steady wage for those hardy few able to keep pace with that unrelenting publishing schedule. Mizuki rose to the challenge, getting his foot in the door with a 1961 series called Kappa no Sanpei (“Sanpei the Kappa”), followed by the even more successful Akuma-Kun (“Devil Boy”).

Mizuki’s big break came in 1965, when an editor of the nation’s most popular manga magazine, Weekly Shonen Sunday, came calling in search of something spooky for the kids. Mizuki re-launched “Graveyard Kitaro” in its pages – to deafening silence. After three months, the editorial department debated cancelling the series. A slow but steady trickle of fan mail convinced them to give Mizuki another shot.

He successfully reshaped the storyline into something better suited for a children’s magazine. By 1968, “Graveyard Kitaro” had built enough of a fanbase to attract the attention of an animation studio scouting for the next big thing. There was only one problem: the title. There were concerns that the grotesque-looking yokai were too far-out for television. And “graveyard” was out of the question for sponsors, who didn’t want to see their products associated with a symbol of death.

Mizuki turned towards his childhood to solve the problem. At a very young age, a predilection for lisping his given name as “Gegeru” instead of the proper “Shigeru” had earned him the nickname “Ge-ge.” The nonsensical phrase also happened to echo the traditional Japanese expression of disgust (“Ge!”) and the croaking of toads, a classic familiar of the yokai.

The serendipitous trifecta allowed Mizuki to surreptitiously (and undoubtedly a little mischievously) inject himself directly into the mix. Re-christening the series Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro, he subtly shifted the concept from scary to silly, and horror to superhero, with Kitaro and his “good” yokai family standing between humanity and “bad” yokai.

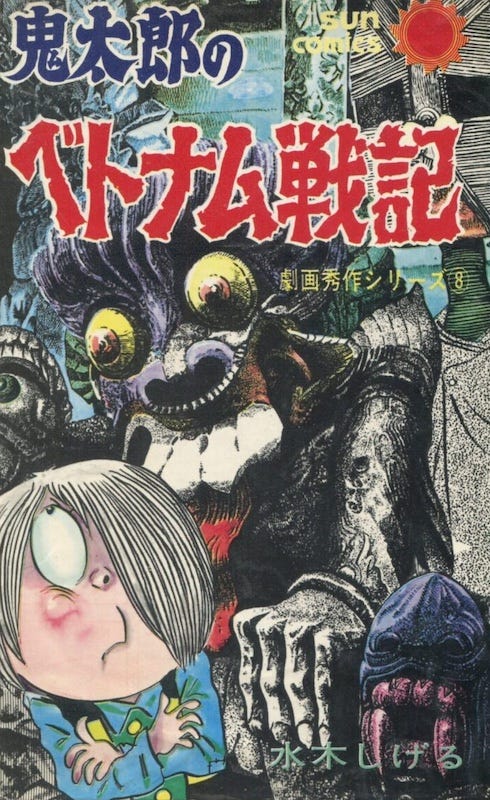

The new formula clicked. Mizuki made folktales cool by re-contextualizing them in modern, often urban, settings. While kids grooved to the spectacle of yokai slugging it out with giant robots in downtown Tokyo, a subtle counter-cultural commentary emerged in references to Vietnam, foolish adult authority figures, and perhaps most importantly, the consistent failure of violent solutions to problems – a legacy of his own wartime experience.

The 1968 animated Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro television series proved more than success: it sparked a nationwide fad, now known as the “yokai boom.” Whatever the sponsors’ misgivings about graveyards and monsters, they certainly didn’t seem to be shared by the children of Japan, who thrilled to the carefully curated “ick factor” of the show. Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro has continued in various forms ever since, spawning no less than half a dozen animated and live-action television series, well over a dozen video games, two live-action films, and The Wife of Ge Ge Ge, a 2010 live-action prime-time TV drama chronicling the struggles of Mizuki’s long-suffering spouse during his rise to fame. Capping it all off, in 2011 the airport near Mizuki’s childhood home renamed itself “Yonago Kitaro Airport” in his honor.

Mizuki’s legacy lives on today not only through his own continuing works (the most recent animated version of which came out in 2018) but their influence on countless others. Kitaro’s family of friendly monsters is an obvious predecessor of the Pokémon, for example. And in the wake of environmental disasters like that of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant, Kitaro’s admonishment of humankind’s hubris and over-dependence on technology seems if anything more relevant today than when first put to paper.

Today Mizuki’s name is virtually synonymous with yokai in Japan, to the point where laypeople often mistake many yokai for his personal creations. The transformation of yokai from terrifying beasts of legend into approachable – and merchandise-able – modern characters is almost entirely due to Mizuki’s handiwork. And here’s to hoping even more of it comes out in translation!

This was a lot of fun. Thank you.

Yet another smart and well-written introduction to an important aspect of life in Japan. Thank you!