The most influential manga in Japan isn’t Japanese

Without Popeye, manga, anime, and video games wouldn’t exist as we know them.

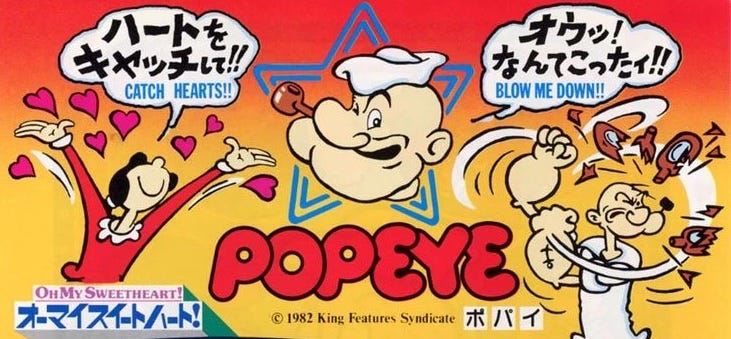

Happy belated New Year! On January 1, 2025, Popeye the Sailorman entered the public domain. He is a quintessential all-American character, one of the nation’s very first cartoon superstars. Charles Schultz, of Peanuts fame, called Popeye “a perfect comic strip.” But you might be surprised to hear that Popeye had an equal, and arguably even greater, cultural impact in Japan. Animated into theatrical shorts and features, he transformed the way a generation of postwar Japanese creators packaged their own fantasies in the burgeoning manga, anime, and game industries. These would then be exported to resonate around the globe, in a ripple effect that can still be very much felt today — if you know where to look.

The artist E.C. Segar introduced Popeye in his popular newspaper comic serial Thimble Theater in 1929. At first, Popeye was merely a foil for the strip’s stars: Olive Oyl, her ne’er-do-well fiancee Ham Gravy, and her brother Castor Oyl. In this first appearance, Castor hires Popeye to row him to a casino for a get-rich quick scheme. This version of Popeye, which is the one that just entered public domain, possessed few of the characteristics we associate with the character today: he wasn’t dating Olive, he didn’t have his rival Bluto, he didn’t eat spinach, nor was he super strong. Still, something about the sailorman resonated with American readers. Segar wrote Popeye out after the story arc ended, but fan mail quickly convinced him to bring the character back. By 1931 he had grown so popular that Segar renamed the strip Thimble Theater Starring Popeye.

Two years later in 1933, Max and Dave Fleischer, of Fleischer Studios, approached Segar to license the character for animation. The brothers had already made a name for themselves by pioneering sing-along cartoons featuring a ball bouncing over the lyrics — a precursor of karaoke! — and by catapulting Betty Boop to stardom. But the Motion Picture Association censors were coming for Betty, with her flapper miniskirts and flirtatious dances. The Fleischers needed a new star, less decadent, less controversial. The everyman Popeye, already a sort of American folk hero, fit the bill.

It was Fleischer Brothers cartoons, shown in U.S. theaters and exported worldwide, that introduced Popeye to a global audience. The Fleischers distilled Segar’s creation down to its basics, eliminating most of the side characters to focus on a love triangle among Popeye, Bluto, and Olive. It was here that Popeye got his iconic “strong to the finish, ‘cause I eats my spinach” theme song, and most of the other traits we associate with him today.

One of the places Popeye proved particularly popular was Japan. Segar passed away quite young, of leukemia, in 1938, so it is likely he never knew this. It was the cusp of World War II, and boycotts and and blockades of Japan were on the horizon. Yet even among our enemies of the day, Popeye inspired.

“I really loved Popeye,” wrote Osamu Tezuka, who first saw the character as a little boy in prewar manga-eiga (as animation was called then) featurettes. “I’d tremble in excitement as I waited for Popeye to eat his spinach and turn the tables on Bluto… The ways in which I make my characters transform into other things is entirely due to my watching Popeye cartoons as a child.” Tezuka incorporated Popeye-inspired content into many of his comics. Some are obvious, like Kutta, a glutton with a striking resemblance to Wimpy; another was a recurring villain named Ham Egg, whose name seems a tip of the pen to Ham Gravy.

And the influence went both ways. When later, non-Fleischer Popeye cartoons were broadcast on Japanese television in the late Fifties and early Sixties, the show was retitled Tetsuwan Popeye for local audiences — inspired, no doubt, by the popularity of Tezuka’s smash-hit manga series Tetsuwan Atomu (Mighty Atom), better known abroad as Astro Boy. The huge success of Popeye in Japan proved that there was an untapped market for full-length animated television series in Japan. This gave Tezuka’s Mushi Productions the boost it needed to bring an Astro Boy series to fruition, meaning that it essentially paved the way for the creation of anime. The two little heroes were in fact so popular that they were often spotted together in unlicensed merchandise, such as these menko game cards.

Another fan was a young Hayao Miyazaki. He is better known for borrowing from the Fleischer Brothers Superman cartoons (most famously, a robot inspired by a 1941 short called “The Mechanical Monsters,” makes appearances in the Lupin the 3rd television series and the animated feature Castle in the Sky.) But their Popeye features left a deep impression on him as well. “Several of the Popeye films are absolutely first-rate,” he wrote in a 1980 essay for a Japanese film magazine, praising “the sharpness of their spatial sense.”

Akira Toriyama, who passed away last year, said of his childhood that “there was a manga boom, so I read Astro Boy, Osomatsu-kun, and the rest. But what influenced me most were things like Popeye and Disney animation.” It’s hard not to see echoes of Popeye in Toriyama’s works — the use of foods for character names in Dragon Ball, the power moves and battles with oversized foes.

But perhaps the biggest influence of all can be felt in the world of video games. Pac-Man creator Toru Iwatani has often said that inspiration hit when he saw a partially-eaten pizza at Shakey’s. But “the idea for the ‘power pellets’ that let you turn the tables on the ghosts, that actually came from how Popeye eats spinach in the cartoon,” he told Famitsu magazine, explaining how video-gaming got its very first “power up.”

Pac-Man hit big after arriving in America in 1980, but something even bigger was brewing. Nintendo designer Gunpei Yokoi conceived the idea for a new sort of game involving platforms after seeing a Fleischer Brothers Popeye short called “A Dream Walking.” In it, Popeye battles Bluto atop a building under construction. The pair climb girders and knock each other from level to level.

“I pulled in this kid Miyamoto, who’d been working on package design for us,” Yokoi wrote in his autobiography. “We pretty quickly came up with a design where Popeye would be at the bottom of the screen, and Bluto at the top. But then the licensing negotiations fell through. So we had to change the characters.” That “kid,” Shigeru Miyamoto, soon transformed Bluto into a giant gorilla he called Donkey Kong, and the sailor into a mustachioed plumber in red and blue overalls. “It was a construction site, so the character had to be some kind of workman,” said Yokoi. “I called him ossan” — old man. Miyamoto preferred “Mr. Video.” For a while, he was “Jumpman.” But in the end, it was the staff at Nintendo of America that gave him the name the world knows him by today: Mario. Perhaps the world’s first Italian plumber of Japanese and American ancestry.

Popeye may not be as popular today as he was in his heyday, but he remains a sort of patron saint of Japanese pop culture. Why on Earth should a comic-strip character dreamed up in America during the Roaring Twenties — and one used as anti-Japanese propaganda during World War II no less — have such a hold on the creative psyche of pretty much the entire postwar roster of manga, anime, and, game megastars?

I see it as a testament to the power of illustrated entertainment and characters to unite us, no matter how bad times get, no matter great our differences may be, no matter how much time between the generations, no matter the distances between us. And it’s important to remember these things as we head into what will undoubtedly be a turbulent 2025.

This was really interesting! Thanks for posting!

Great piece, Matt! Love these explorations of little known pop culture connections. Enjoyed the read!