Super Galapagos

In a world driven mad by tech disruption, Japan’s having fallen behind is a superpower

Galapagos is, of course, an archipelago off the coast of Ecuador, named for the giant turtles that are its most famous residents. It is famed for its remoteness and for how the wildlife evolved to match the peculiarities of that local environment. But it has another meaning in Japan. Engineer and “open source guy” Shuji Sado jokingly started calling Japan “Galapagos” in 2004. But the term didn’t enter the popular lexicon until 2007, when a truly transformative product went on sale, unseating Japan from its role as the king of consumer technology. It was called the iPhone. In the wake of its success, pundits glumly began referring to their nation as suffering from “Galapagos syndrome.” The idea was that Japan had grown too insular, too focused on the peculiarities of its local market to compete globally.

Until that point, the dominant narrative about Japan was that it had gotten to the future a little ahead of the West. Books like Japan as Number One (1979) and films like Blade Runner (1982), with its Tokyo-esque Los Angeles of the future, set the tone: the coming century would be Japanese. This image held firm even as Japan’s economic bubble burst in 1990, ushering in decades of depression of the financial and psychological varieties. As late as 2001, the sci-fi writer William Gibson could still remark that “Japan is the global imagination’s default setting for the future...The Japanese seem to the rest of us to live several measurable clicks down the time line.”

The iPhone changed all that. In the years after, an even more cynical narrative emerged. There’s a joke that captures it perfectly: Japan has been living in the year 2000 since 1980... And it’s still living in the year 2000 today. Whether in social media, generative AI, scientific publishing, personal wealth, even (gasp) dance music – reports pile up of a Japan falling further and further behind. “Japan used to be a tech giant,” lamented CNN in August. “Why is it stuck with fax machines and ink stamps?”

Let’s put aside for a moment the fact that America, Germany, and other high-tech nations still use fax machines, too. First, the story went that Japan was ahead of the curve. Then, the story went that the rising sun had set. Now, yet another viewpoint has been gaining traction on social media. It’s called the “Japan really is living in 2050” meme.

At first blush, this sounds like history repeating. But these videos (and they’re inevitably videos) actually focus on everyday consumer products and services. Things like convenience store condiment packets, refrigerators with doors that open from either side, toilets whose lids lift automatically, automated cash registers, train seats that rotate, and…uh, single-serving yogurt. Never mind that most of these things exist in some form abroad. Or that they are expressions of convenience rather than futurism. The yogurt one got 2.6 million views on TikTok.

The fascinating thing about the meme it isn’t whether it’s true or false, but rather what it says about those sharing it. This is Japan as neither futuristic utopia nor failed empire, but simply a nice place to live. Which can probably be interpreted as a reflection of how bad things are getting for young people abroad.

Once the West feared Japan’s supposed technological superiority. Then came the schadenfreude over Japan’s supposed fall. Now a new generation is projecting upon the country an almost desperate longing for comfort. And is it any wonder? The meme centers on companies producing products that make the lives of consumers easier. That must feel like a dreamy fantasy to young folks who’ve only known life in an attention economy, where corporations are the consumers and they’re the products.

To them, Japan isn’t in the past or the future. It’s a very real place — a place where things haven’t gone haywire. This is Japan as a kind of Galapagos, but not in a pejorative sense. Rather, it’s a superlative, asking, a little plaintively: Why can’t we have nice things like this in our country?

* * * * *

I remember the arrival of the iPhone in Japan well, because I was here when it happened. 2007 was an interesting moment. The anonymous message board 2channel had entrenched itself as the preferred online hangout for young Japanese, spawning new trends like netto-uyo (“net right wingers”) and netto-ijime (“net-bullying.”) A then-unknown anime director by the name of Makoto Shinkai had just released a groundbreaking film called 5 Centimeters Per Second. And Shigeru Ishiba, then Minister of Defense, made headlines by remarking that if Godzilla hypothetically attacked Japan, the self-defense forces would be legally justified in fighting back.

When the iPhone dropped in America that January, it sparked a consumer frenzy. SoftBank spent the next six months laying the groundwork for its release in Japan that June. As a lifelong Apple user (I’d grown up with an Apple II+ and a IIGS in my home, then lugged a Macintosh Portable to university) I anticipated its arrival with excitement.

It was right around this time that Sony announced a new product. What might that titan of consumer electronics, the creator of the boombox, the Walkman, the Trinitron, the PlayStation, Aibo, and so many other innovative products, be bringing to market?

Its name was Rolly. Sony touted it as a robot, but it was really an egg-shaped MP3 player that “danced” in tune with whatever music you loaded onto it, or that could be remote controlled with a cellphone. At a shop in Akihabara I watched the thing listlessly roll about a tabletop, flashing its LEDs and flapping its ear-like wings to tracks by Hikaru Utada and Arashi. It was cute enough. But in the face of the incoming iPhone, it felt utterly and totally irrelevant. It reminded me of that scene from Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions where an alien lands on Earth bearing wondrous technologies, but gets ignored because it can only communicate by farting and tap-dancing. The contrast between Rolly and the Walkman or the PlayStation felt stark, even a little unnerving. Revolution was on the horizon, and this was the best Sony could do? So this, I thought, was the “Galapagos syndrome” I’d been hearing about.

For a long time, when it came to communication technologies, Japan really had been “several measurable clicks down the timeline” compared to West. Japan is where early digital compulsion-loops, the building blocks of attention economies, were first honed in video games. It was the first society where mobile texting became a youth phenomenon. It was where emoji were invented. It was the first nation to experience how fast-ramping an entire population online might affect the national conversation, back in 1999, which is when both the “i-mode” mobile internet service and 2channel debuted. They may have been doing it on flip-phones, but the Japanese were experiencing the internet-in-your-pocket lifestyle a decade before the West.

So watching Japan totally miss inventing the smartphone felt less like a letdown than some kind of betrayal. And Sony had been so, so close. They had released a proto-smartphone in 2002. Japan’s best-selling mobile phone in 2006 was the Sony-Ericsson “Walkman Phone,” a fusion of MP3 player and cell phone. Sony even owned its own record company! Then the iPhone dropped in 2007, laying waste to the entire Japanese phone market like the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs.

No exaggeration. Three years later in 2009, Apple owned 72% of the market for mobile phones in Japan. The following year, that rose to 90%. It was brutal. People began calling the bespoke domestic models that had once dominated the scene gara-kei, short for “garapagosu keitai” – Galapagos mobiles.

But looking back with the benefit of hindsight, the arrival of the iPhone wasn’t precisely the debacle for Japan that it initially seemed. Had it been any other product, from any other company, it might have been. But the iPhone was perhaps the single most Japanese piece of technology ever to be invented by an American company. Jobs “didn’t want to be IBM,” recalled John Sculley, who served as Apple CEO from 1983 to 1993. “He didn’t want to be Microsoft. He wanted to be Sony.” Jobs so worshipped at the altar of Sony’s consumer electronics that initially attempted to name the iMac the MacMan, after the Walkman, until someone convinced him he’d decided otherwise.

The iPhone sweeping the world was a triumph for Jobs, for Apple, and for Silicon Valley. But it was also a quiet triumph for Japanese sensibilities, aesthetics, and lifestyles. Thanks to it, the whole world started living a lot more like the Shibuya schoolgirls who’d pioneered mobile gaming, texting, emojis and selfies back in the Nineties. The iPhone was American. But the new lifestyles it delivered were the ones Japanese had already been living for a decade.

The critics were right in that the iPhone signaled the end of an era for Japan, putting a definitive period on the end of the sentence, Japan as factory to the world. What they missed is that it also signaled the start of something new: Japan as global influencer.

* * * * *

I agree that Japan is a kind of Galapagos, in the sense that it can be oblivious to global trends. But I disagree that this is a weakness. The reason being that nearly everything the planet loves from Japan was made for by Japanese, for Japanese in the first place.

Looking back, this has always been the case. Whether the woodblock prints that wowed the world in the 19th century, or the Walkmans and Nintendo Entertainment Systems that were must-haves in the Eighties, or the Pokémania that seized the planet at the turn of the Millenium, or the life-changing cleaning magic of the 2010s, or the anime blockbusters Japan keeps unleashing in the 2020s – they hit us in the feels, so we assumed that they were made just for us. But they weren’t.

As I wrote a few months back, Japan’s creators have traditionally never paid much mind to foreign consumers. Kozo Ohsone, engineer of the Walkman, told me that he built the first one simply to see if it could be done; Sony initially had so little faith in its prospects that they made only 30,000 in the first production run. Hayao Miyazaki has said that he is “baffled” by the popularity of his work abroad. Shigeru Miyamoto, creator of Mario, has said in interviews that most at Nintendo initially assumed Pokémon would only be released in Japan.

The editor of a major manga magazine put it to me succinctly: “I don’t think we should worry about foreign audiences. I don’t mean that we should be ignoring them. I mean that trying to create something specifically for them doesn’t work. It has to succeed in Japan before it can succeed globally.”

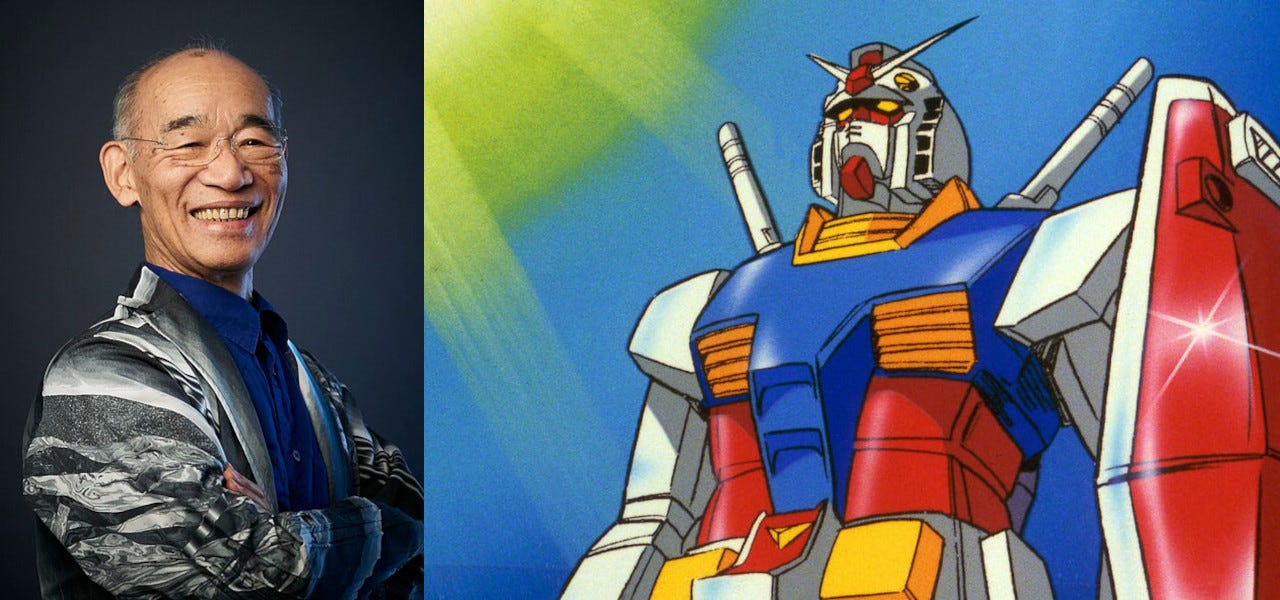

This makes me recall a moment from 2014, when I had the chance to meet a childhood idol of mine: the anime director Yoshiyuki Tomino, creator of Mobile Suit Gundam. The occasion was a press conference for an international co-production that never came to fruition. After, I asked him about the government’s Cool Japan initiative to promote Japanese content abroad.

“I hate that term,” he said. “There’s no way the government can make anything ‘cool.’ Anime developed on its own without any help. The moment a bureaucracy focuses on creativity, creativity dies.”

“Japanese content has a local flavor,” he continued. “That sense of culture, that localness, is why it has sold for so long. People never expected any of it to sell abroad. They never promoted it because they were embarrassed about it. Japanese didn’t realize that proudly embracing the differences and marketing it to people of other cultures was a way of doing things.”

They’re realizing it now. Anime exports are now equivalent in size to that of semiconductors or steel. Revenues from foreign markets surpassed those of the domestic market in 2023. The content industry is growing wildly, attracting all sorts of people who’ve never shown much interest in manga or anime or games before, from politicians to venture capitalists. This brings opportunity, but also pressure. As cartoons begin contributing to GDP, politics come into play. The LDP has spoken of wanting to triple the size of the content industry by the end of the decade, and private equity firms are already placing their bets.

But true cool, as Tomino says, can’t be bought. It has to be earned. This is the double-edged sword of Japan’s pop-cultural momentum. It didn’t set out to become a soft-power superpower. It emerged as one organically, thanks to the authenticity of its cultural products. And that authenticity is a result of Japanese producers doing their own thing, for local consumers, with little if any oversight or support from the authorities.

Japan’s market for fantasies is crowded and ferociously competitive. What survives is the fittest – and often the weirdest, as in the least likely to emerge from a corporate boardroom. Demon Slayer didn’t succeed because of government support or venture capital. It succeeded because Shueisha, over many years, created a system for platforming talented independent creators, and giving readers the chance to choose their favorites from among many rivals. Shueisha has used this system to create dozens of global hits. Meanwhile, witness how Netflix, an entertainment behemoth whose revenues dwarf Shueisha’s, hasn’t landed a single zeitgeist-level hit from the dozens of anime titles it has directly funded.

This indirectly illuminates another aspect of the “Japan is really living in 2050” meme: there are upsides to living in a country that hasn’t become a pay-to-play petri dish for the social experiments of techbros and billionaire CEOs. Perhaps this is due in part to the fact that there are a lot less of them here. As Warren Buffett put it recently, Japanese executives are “far less aggressive about their own compensation than is typical in the United States.” The head of the US wing of Seven & I Holdings, which operates the world’s 7-Eleven stores, took home $49 million in 2024 — almost 23 times the salary of the CEO of the parent company in Japan. For all of its many and varied flaws, Japan does not feel like a place where CEOs occupy a different plane of existence from mere mortals.

So this is my advice. Japanese creatives should keep doing exactly what they have been doing: making things for themselves first, and worrying about global markets later. And all of us need to stop thinking about Galapagos as syndrome, because a measure of isolation and dislocation from global trends is Japan’s secret to success. Japan may no longer be the global imagination’s default setting for the future, but then again, the future isn’t as bright as it used to be. In an era of incessant disruption, sitting out the tech wars seems less like a syndrome than a savvy strategy. It’s certainly playing a big part in the nation’s global charisma of the moment. It’s time for Japan to acknowledge this, and embrace its role — as a super Galapagos.

Great article. And I agree that Galapagos is not necessarily a weakness. I liken a lot of J-pop today to “Galapagos music” - charmingly out of touch with the rest of the world. Where else can kids songs like Paparika become popular? Or while K-pop plows forward with visual beauty, many J-pop singers like Ado hide their faces. Thanks for sharing your insights.

Oh man, I remember the iPhone 3G debut in Japan. I sat in line over night outside of the Harajuku SoftBank for...27 hours (I think?) I even got to shake Masayoshi Son's hand at some point that evening, when he visited the line.

I remember local pundits predicting that the iPhone would fall flat in Japan because "people like the tactility of buttons" and that "Japanese women would never take to touch screens because their long nails would make it hard to use." Boy, were they wrong.

I was a combat sports journalist (and grad student) at the time, reporting on the twilight days of the kakutogi boom for an international MMA news site, and so the iPhone was a godsend of a reporting tool. That need to report at the speed of information was why I sat in that crazy line.

While I very much agree that billionaire oligarchs have made life pretty unpleasant in the West, it's interesting that it was one of Japan's own billionaires in Son-san that pushed to bring the iPhone to Japan at a time when the likes of NTT Docomo and KDDI were quite content with doing their own thing. While very Galapagos indeed, I wonder: do you think that the introduction of the iPhone to Japan was a good thing in the end?