Politics, Chaos, and Cup Noodles

The eerie parallels between Japan's Sixties and America today

The shooting of Charlie Kirk has thrown an already divided America into deeper existential turmoil. Did you know that he spent the weekend before his death in Japan? Sanseito flew him in to address their troops. That they did so should tell you everything you need to know about their politics, but if not, here’s a refresher. Predictably, they’re going to monetize the video, selling access for 10,000 yen. The grift continues.

Making sense of American society today often feels like an exercise in futility. But this weird cross-over between American and Japanese culture wars got me thinking. I went out and collected some quotes that seemed to capture the current moment.

“The country is headed in the wrong direction.”

“I’ve totally lost faith in universities.”

“I’ve lost any hope of attaining the future I imagined for myself.”

“Life is empty and the future is hopeless.”

Here’s the trick: I didn’t pull these off of TikTok or social media. These comments are almost six decades old. They’re the voices of Japanese university students in the late Sixties, who faced a crisis a lot like America’s, and who dealt with it in a similar way: by embracing extreme politics, and even political violence. (This is a solid overview of the era by Eiji Oguma, and it’s from where I quoted the above.)

Japan? Safe, sane (for the moment), tourist wonderland Japan? Doesn’t Hello Kitty live here? It’s hard for many to imagine such political chaos unfolding in Japan. But it did. And the broad beats of that chaos echo our moment, in many ways. The angry young Japanese of the Sixties went left (sometimes very far left.) The angry young Americans of today seem to be going right (or, at least, the young men seem to be.)

Yet something’s amiss. If there truly were a conservative wave among the young people of America, you’d expect them to be overjoyed about the way things are going in the U.S. right now. But they aren’t. And the President’s approval ratings are plunging as a result. As you’ll see, Japanese protestors of the Sixties weren’t nearly as progressive as their slogans might suggest. And this makes me wonder if young Americans are really as conservative as surveys report.

But something does unite these groups, across the gap of time. What they share isn’t politics so much as a sense of their respective societies having failed them, and that the only way forward isn’t by building, compromising, or co-opting but destroying the status quo. For their only shred of hope lies in the fantasy that something more hospitable might emerge from the rubble.

Japan went through this in the Sixties, through a grass-roots student protest movement; America is experiencing it now, with the twist that the urge to dismantle and demolish is coming from the top down. Our two nations have been locked in orbit since the end of World War II, influencing and reacting to one another, so there’s a kind of yin and yang, of separate experiences reflecting and refracting across time and space. If you’re an American searching for a light at the end of the tunnel, a roadmap of how things might play out, there are worse places to look than Japan of the Sixties. Because for all the chaos of our current moment, one thing never changes, and that’s human nature.

You’ve got to understand, first, how Japan of the Sixties was nothing like the Japan we know today. Everyone was a lot poorer. Huge numbers of young people raised in tight-knit rural agrarian communities emigrated to Tokyo for their shot at success. The big city wasn’t kind. Students found themselves stripped of all social ties, alone, lost on overcrowded campuses, unable to find career-track employment in a market oversaturated with baby-boom grads. And since most of these new arrivals were men, their chances of making a connection with anyone of the opposite sex were low indeed. There were no convenience stores, no fast-food joints, no arcades. Grownups back then didn’t watch anime or indulge in hobbies. You were expected to study, or not, and drink. Or, if you were lucky, work and drink. “Pink” film at the local theater? Sure, why not.

A triad of fatalism about the future, loneliness, and escape through substances or porn reflects how profoundly disconnected many Tokyoties felt in the late 1960s. It’s also a cycle intimately familiar to anyone living through the 2020s. And it links to something else intimately familiar: the politicization of young people.

Students quoted Marx, sang The Internationale and We Shall Overcome, and marched in antiwar demonstrations. But were they Marxists, leftists, or even progressives? Some certainly were. But there was a decidedly conservative bent to the movement, too -- particularly when it came to women. Male leaders often pressured female comrades into traditional roles such as preparing food; sometimes they even pressured them into arranged relationships. The most popular forms of entertainment were yakuza movies and manga that celebrated traditional masculine values and revered asceticism, all in service of fighting for what’s right. In some ways, you might even say it resembled the “manosphere” of today.

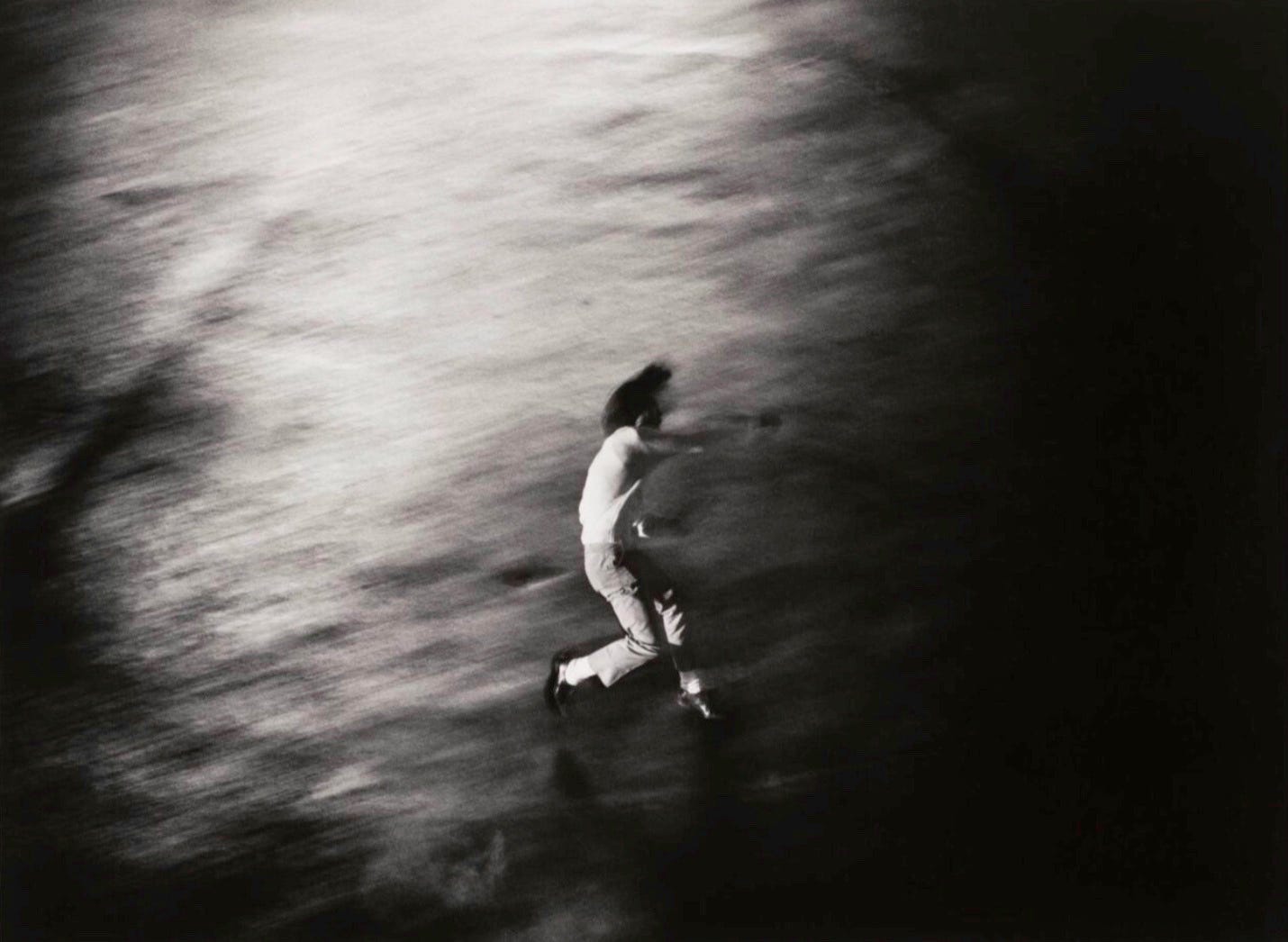

Groups of angry students and workers massed under the banner of anti-war and pro-labor causes, launching protests that sometimes turned violent, even deadly. Some participants were true believers. Others, perhaps more, were in it for thrills: of meeting new people, or picking up girls, or clashing with police. “We didn’t care about Marxist philosophy,” recalled the anime director Mamoru Oshii in 2016. “We just wanted to wreck everything.”

The government — led, in the late Sixties, by Eisuke Sato, great-uncle, not coincidentally, of Shinzo Abe — began cracking down. It issued draconian laws in the name of re-reestablishing public order, militarizing the police and empowering them to conduct operations on university campuses. The students fought back until the bitter end, when riot police finally broke through their barricades. The dreary Tokyo of the Oshii-produced Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade, in which armored soldier-cops battle undeground rebels captures the vibe, if not the reality, of those days. The general sense was that Japanese society teetered on the knife-edge of chaos, even civil war. There’s history rhyming again.

So what happened? How did we get from that drab, violent, Jin-Roh esque Tokyo to... Chiikawa, cosplaying Prime Ministers, and crowds of tourists?

The short answer is that the vast majority of student demonstrators didn’t really want to tear the system down, even if that’s what they claimed in interviews. They wanted to be seen. A majority of students surveyed at the time framed the struggle in intimately personal terms: they were fighting “to assert themselves” or “to transform themselves.” Less than one percent expressed any interest in working in politics. It wasn’t really about politics. It was about throwing a monkey wrench into a society they felt was failing them. “Once we've taken over the state,” said one organizer “All of those problems will sort themselves out.”

They never got their chance. Those government crackdowns made protests a lot less palatable to casual participants, for one thing. And then there was the Mt. Asama Lodge Incident. In February of 1972, a group of die-hard radicals murdered fourteen of their own members in a loyalty purge, went on the run from the police, and barricaded themselves in a mountain hotel. The standoff, broadcast on Japanese TV, transfixed the nation. By the end of it two police and one civilian were dead.

This moment of public political violence was every bit as shocking to Japanese as the Kirk assassination was to Americans. So was the idea that extremists were turning on fellow extremists for not being extreme enough — which seems, at the moment, to be the case with Kirk’s murder as well.

But there was a seed of hope amidst that chaos, one nobody really noticed at the time. In between dodging of gunfire, spraying of fire-hoses, and swinging of wrecking balls at the lodge, the police had to eat. It was too cold for bento boxes. Enter Cup Noodles, only released by Nissin just a few months prior, which could be prepared and served using hot water. The sight of the officers fortifying themselves on television sent sales through the roof.

Today, the world knows Japan for things like Cup Noodle — ingeniously designed, compact, playful — and not for political violence. That’s because Asama represented a turning point for Japan. The shocking act of political violence that happened in Utah last week feels like a turning point for America, too. Or, at least, many of our politicians and influencers are trying to paint it that way. As you listen to them, as you read distressing headlines, I want you to remember that Japan turned away from its culture wars, and that it did so for a singular reason: hope.

I don’t mean this in some new-age-y peace-and-rainbows sort of way. I mean it concretely, and more specifically economically. Most of the student movement’s participants weren’t really radicals. They didn’t really want tear society down, let alone kill anyone. They wanted in. They wanted jobs, homes, partners, retirement plans. They wanted tickets to the gravy train. And they got it.

For despite all the turmoil on the streets, Japan as a nation continued growing by leaps and bounds. It had already emerged as the planet’s second largest economy by 1970. Suddenly, all of those kids who’d felt left out had everything they wanted. With labor in huge demand, they could start careers, families — in other words, build futures. The cynics (and there are many) lament how quickly supposed radicals transformed into salarymen. But no matter how you feel about Japan’s rip-roaring greed-is-good Bubble Era, it sure beat violence in the streets.

So. There are many parallels between Japan of the Sixties and America of the moment. Japan healed. I want to believe that we can, too. Japan’s salvation came from the fact that its young people started to feel hope for the future once again. Our salvation can only come from the same. The details will necessarily differ, of course, because of our differing cultures, our technologies, our times. Nevertheless, human nature never changes. We hunger for brighter futures. And cultivating that hope, somehow, against all odds, even if feels like an impossibility, is the single most important thing we can do right now. Because the stakes are too high to do anything else.

Very interesting - when I first arrived in Japan as a child, late 1972, my parents were both university lecturers and the student protests were almost over and as you say, a more radical, terrorist activism had taken over. It made mainstream Japanese very shy of overt political expression in the decades after - one reason for the LDP's dominance I suppose. Some of the now very respectable leaders of the Japanese permanent resident community in the UK were student radicals back then, and came to the UK in the early 1970s in full hippy mode and set up businesses here. I doubt if young Japanese will do the same thing now - they seem very reluctant to move abroad and the UK and US are having their own anti-immigrant protests too.

Nice analysis. A possibly relevant anecdote: When I was writing Canon ad copy for Hakuhodo back in the 80s, I was told that then Canon Chairman and CEO Mitarai-san was a leader of Zengakuren.