Japan, the "most AI friendly country in the world"

The country's leaders are gung ho for AI. But will it kill the golden goose of its content industry?

Just a reminder that I’m continuing to record “audiobook” versions of my essays. Love ‘em? Hate ‘em? Let me know what you think! And stay tuned as I’m planning to start releasing video excerpts on my long-dormant YouTube channel in the near future.

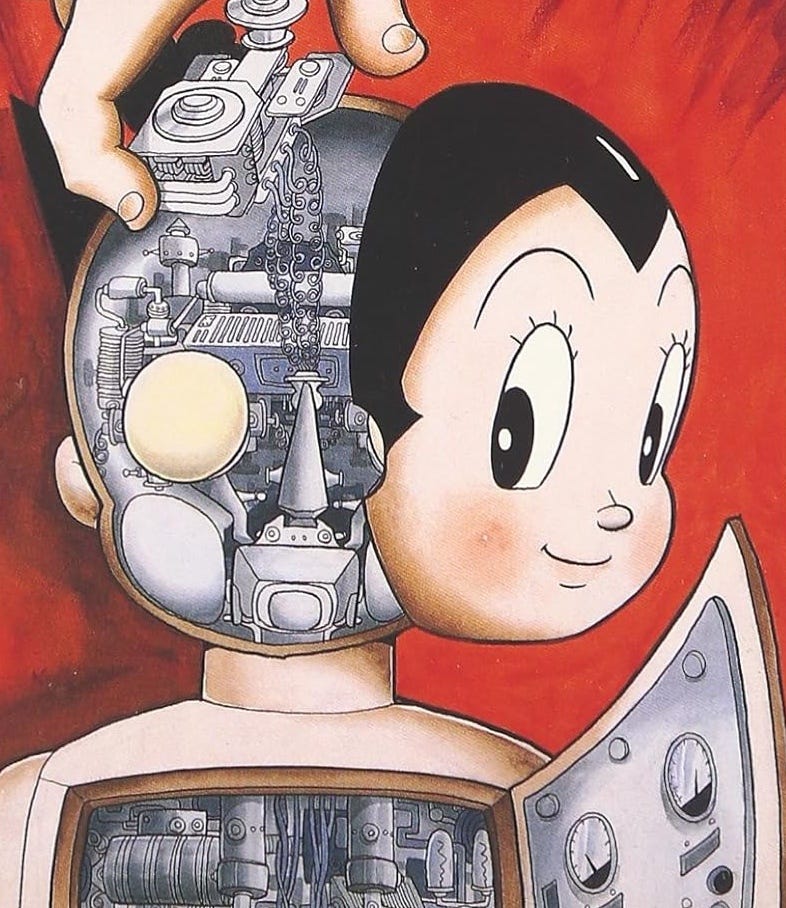

In 1963, a medical student turned manga artist named Osamu Tezuka coined the term “a…