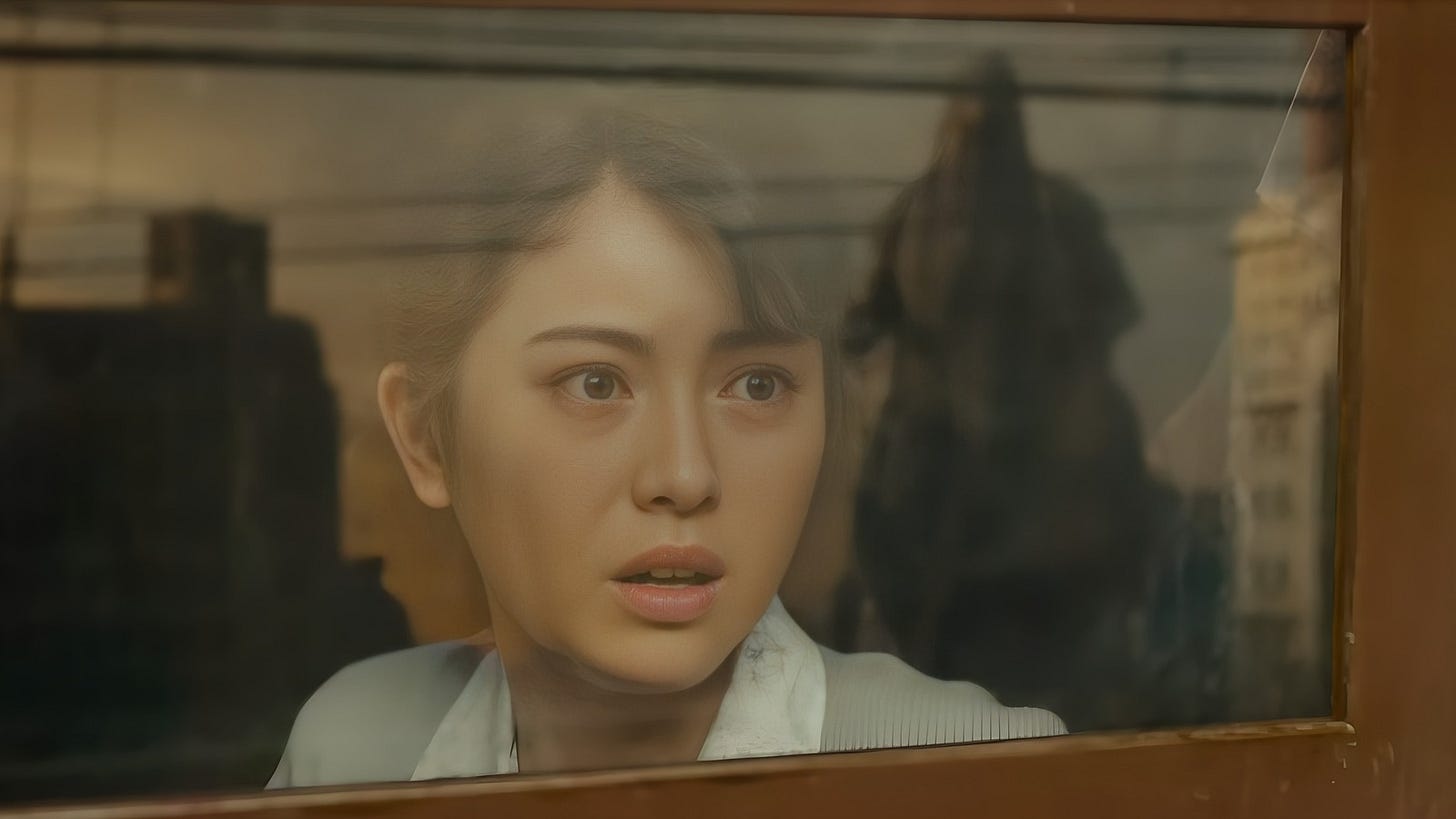

“Godzilla Minus One” Doesn't Quite Add Up

Takashi Yamazaki delivers an exquisitely rendered postwar Japan. But does his re-envisioning of history go too far?

Broadly speaking, Godzilla features can be divided into two categories: the statements, and the slugfests. One might further subdivide them into Japanese and American categories, as movie-makers in each country have such fundamentally different philosophies. But let’s put that aside for now, and focus …