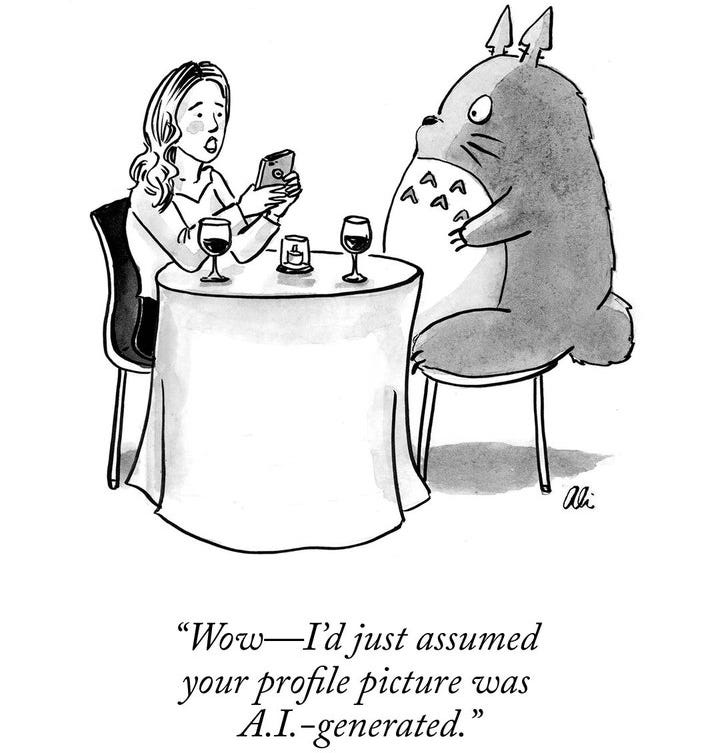

Ghibli, glibly

What does Hayao Miyazaki really think about AI?

First, a quick heads up. March marked two years since I launched this newsletter. (How far we’ve come since the Astro Boy fashion craze of 2023.) In that time, I’ve learned that being a newsletter writer is a privilege. It’s also a tough business. I deeply appreciate each and every one of you who has subscr…