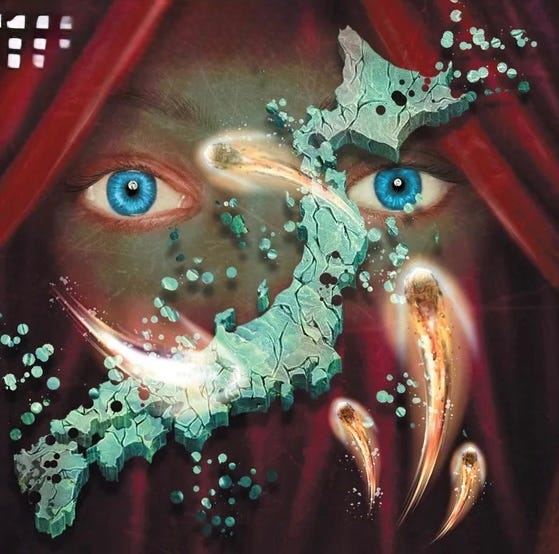

Chemtrails over Kyoto

What stops conspiracies from hijacking the conversation in Japan?

A few weeks back I was in Kyoto for Bitsummit, the annual event for indie game developers, and took a taxi from my hotel to the venue. Along the way, I used the reporter’s trick of asking a cabbie for his thoughts. We bantered about the hordes of tourists that have profoundly transformed the vibe of the city, and I was surprised to hear that locals, des…