Anime's money problem

Anime is blowing up. It's also facing an existential crisis.

In the Twentieth century, Hollywood movies and rock & roll won hearts and minds around the world. But now the locus of cool has shifted from West to East, and to Japanese anime and manga in particular. Japanese pop culture changed the direction of my own life, so I get this on a visceral level. But most of that time — most of my life! — anime and manga were subcultures, for squares rather than the tragically hip. So all of this recent exuberance about anime from society at large triggers me. Not in an “I was into it before it was cool” way, but rather in the form of a little voice inside my head, one asking inconvenient questions. Like: Is this sustainable? Is it sustainable in a way that keeps anime anime? Or are we in the middle of a bubble that’s going to pop like that one at the beginning of Akira?

Anime and manga are hot topics at the moment. Their earnings are certainly on the minds of business people, as indicated by a pair of stories that hit financial papers last week. First, Nikkei Asia reported that the domestic anime industry is worth 339 billion yen a year — that’s two billion dollars USD. Which sounds pretty impressive, until you read The Wall Street Journal’s report that the global anime industry is now worth twenty billion USD a year — ten times the domestic market. Estimates are this will grow to sixty billion by the end of the decade. This is why Sony paid more than a billion dollars for the streaming platform Crunchyroll in 2021, and Blackstone paid 1.7 billion for Japan’s biggest manga streaming site earlier this year.

The cultural aspects of the mediums are attracting a great deal of attention, too. Polygon wrote of anime being bigger than the NFL among Gen Z, and The New York Times followed this up with reports of Gen Z NFL players taking anime onto the gridiron themselves. Japanese cartoons have made headlines before, but now they’re going toe-to-toe with the all-American pastime. And not even just American! In order to engage with “the pop culture so beloved by our young people,” the Vatican — yes, that Vatican — just unveiled a super kawaii anime-style mascot, complete with doe eyes and rosary. So there’s something different this time around, and gatekeepers are finally paying attention. I know from conversations with editors and writers that several major magazines are preparing big features on anime and manga right now. Again: hot topics.

On the other hand, we have… The United Nations. Which in a recent report announced that it believes the anime industry is on the verge of collapse, due to the low salaries and poor working conditions of the people actually making the stuff. A third of the industry is forced to work without any protection from labor laws, making them “ripe for exploitation,” in the UN’s words. The reports of how bad young animators have it are nothing new, but a UN working group identifying their plight as human rights issue is — and yet another example of how much anime is blowing up on the global stage.

This isn’t the first time a form of Japanese entertainment has swept the planet. That would be the video game. There are striking parallels between the 20th century fad for games and the 21st century boom for anime and manga — and many lessons to be learned.

The story begins with a bubble bursting: the video game crash of 1983, which cleared the U.S. marketplace of virtually every domestic game-maker. As a result, Nintendo arrived on American stores in 1985 with close to zero competition. By 1993 the company controlled 80% of the U.S. market for home video game consoles. One out of three homes owned an NES, more kids surveyed could name Mario than Mickey, and Nintendo’s CEO was flush enough to purchase the Seattle Mariners on a whim. Mama mia!

For the rest of the Twentieth century, Japanese firms, led by Nintendo, and Sega, and Sony, plus countless studios of varying sizes that made games of varying quality, dominated the American, and global, video game marketplaces.

Then, in Street Fighter II fashion, came another challenger.

Microsoft’s Xbox arrived in November of 2001. At first, it didn’t fare particularly well against Sony’s Playstation 2. But Microsoft had deep pockets and patience and learned from the experience, and began chipping away at Japan’s seemingly unbreakable dominance of the international gamer imagination. Subsequent iterations of the Xbox enticed Western developers to the platform, who nourished megahits like the Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto, iconic franchises that outsold many Japanese games. By 2010, the Japanese industry was widely seen as being in a rut.

Today, twenty-three years after the Xbox’s debut, Japan’s products account for just 10% of a global marketplace worth 280 billion USD. Admittedly this is not chump change, but it is a dramatic shift from when Japanese game-makers pretty much dictated how the planet gamed.

So what happened, and why is this relevant to anime?

In a very simplified nutshell, kids raised on decades of Japanese games grew into adults who’d absorbed all of the lessons the masters had coded into their products. They began crossing Japanese-style craftsmanship with Western sensibilities. This proved particularly fruitful with subjects seen as taboo in Japan, like blood, gore, and crime. (Grand Theft Auto is very much not a thing in Japan; San Andreas was censored to the point of becoming practically unplayable in Japanese.)

Now, while hits from Japanese makers abound, the most important and influential titles tend to originate abroad. Sales charts show this: only one out of the ten bestselling games of 2023 was Japanese. Japanese studios reliably churn out hits based on classics; that singular 2023 top-ten hit was The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom —the twentieth (!) title in that series. A worthy inclusion, to be sure. But today, the real technological innovation is happening outside of Japan. In other words, the Japanese game bubble popped quite some time ago.

And there’s more: some of the most “Japanese” games are now being made outside of Japan, by non-Japanese teams. 2020’s Ghost of Tsushima was set in ancient Japan but developed in Washington State, and the upcoming Assassin's Creed Shadows, set in, once again, ancient Japan, but developed in Quebec. So Japanese gameplay AND cultural sensibilities are being emulated outside of the country now.

Anime and manga currently occupy a socio-cultural and economic position that resembles Japanese video games in that golden era of the 80s and 90s. Japanese companies dominate, because they serve niches that aren’t being satisfied in foreign marketplaces. Even as American graphic-novel offerings mature, there’s nothing comparable to the sheer granularity of Japanese illustrated entertainment, with offerings targeting boys and girls; children, tweens, adolescents, and adults; straight, queer, and everything in between and beyond; and sports, vocations, and avocations of all kinds. If you’re a fan of certain genres — gay romance, basketball, people with chainsaws for heads — you’re pretty much compelled to watch anime or read manga.

This helps explain the dominance of the anime and manga on the global stage. But will it last?

As the numbers show, more of this content is now being consumed outside of Japan than in. The Japanese creative industry has its finger on the pulse of what young consumers want, but there are limits to how much content the nation’s fantasy-industrial complex can produce. A certain percentage of foreign fans raised on the genres are inevitably going to grow up to want to create something of their own, much as gamers did. We are already seeing increasing numbers of non-Japanese working at anime studios. And the success of Japan-inspired American animation such as Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse or Blue Eye Samurai, the co-creation of a Japanese wife and American husband team, show that is is already starting to happen.

This is a good thing! I’m part of a cross-cultural husband-wife creative team myself. I think these kinds of things are great, even if the actual products aren’t always my cup of green tea. But from talking to friends on anime production committees, I know that the demand for Japanese anime is wildly outstripping supply capabilities. Even if you has full funding, it now takes several years just to get a new series slotted for production. Money alone isn’t enough to jump the queue — unless you have enough to buy a studio outright. Bandai Namco figured this out a long time ago, with their 1994 acquisition of Sunrise (today known as Bandai Namco Filmworks.) Now we’re seeing other big players following in their footsteps. For instance, Toho has been emulating its biggest star and gobbling up anime studios and distributors.

If demand continues skyrocketing for anime abroad, and Japanese studios can’t keep up, others will step in to fill the gap with “anime,” scare quotes intended. And it doesn’t help that the anime industry is fundamentally broken in many ways: overwhelmed with animators who are overworked, and, as the UN notes, also almost criminally underpaid to boot. These issues need fixing. But I’d like to see Japanese fix them themselves, rather than vulture capitalists and private equity that inevitably accompany Wall Street setting its sights on the Next Big Thing. (Yes, I’m still salty about what they did to Toys ‘R’ Us.)

Now, to (cos?)play devil’s advocate, what are some reasons why all of this might not come to pass? The biggest is that anime and manga are produced in well-established systems that are very peculiar to Japan. These include factors like Japan’s media marketplace, which is set up to make it far easier to merchandise and advertise products to children as compared to the US. And Japanese manga publishers operate in fundamentally different way than American comic-book companies.Weekly Shonen Jump, for instance, pioneered the use of big data from readers, and using it to direct the creative process, long before streaming media made that the norm for filmed content in the West.

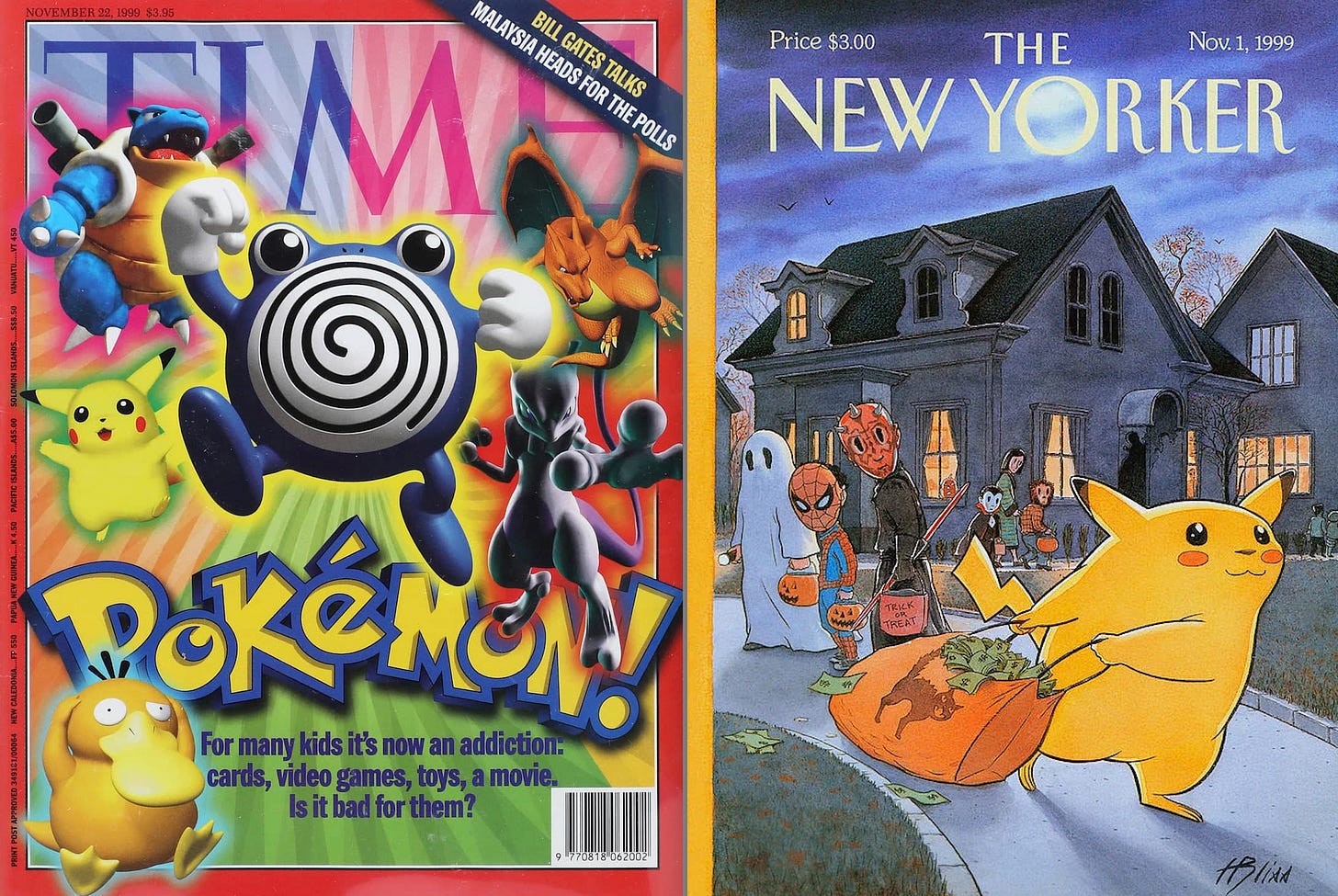

Manga and anime are much more than aesthetics or styles; they’re products of a very unique creative-business ecosystem that doesn’t exist anywhere but Japan. (This is a big reason Pokémon hit so hard back in 1999: it arrived fully formed, having been carefully developed into a multi-platform blockbuster over several years in Japan first.)

So Japan’s illustrated entertainment is booming. But there are cracks in the foundation upon which this success is built — cracks which the influx of outside money could well exacerbate rather than fix. I want to see manga and anime flourish in the way in which I first enjoyed them, which is as products of, and reflections of, Japan. And doing that means making sure the money starts going into the pockets of the people who actually make it. Whether that will actually happen is an open question. It is in fact THE question, an existential one for the Japanese fantasy-industrial complex.

I am sad to say I may have directly contributed to Japan’s demise here! Last year a German company paid me to record me playing my conch for a Sengoku-jidai game they were making. I guess I should be more careful! (/sarcasm)

I kind of had this feeling that if the Japanese animation industry were to fail, perhaps the gap in adult animation will be filled in by western countries and other nonwestern countries will handle the kiddie animation sector themselves instead.