A History of the World in Japanese Toys

Can you decipher the 20th century by looking at Japanese toys? I can try!

“Without shadows, there would be no beauty,” wrote Junichiro Tanizaki in his classic In Praise of Shadows.

I’d say the same thing about toys. Toys are play in physical form. And without play, life isn’t worth living.

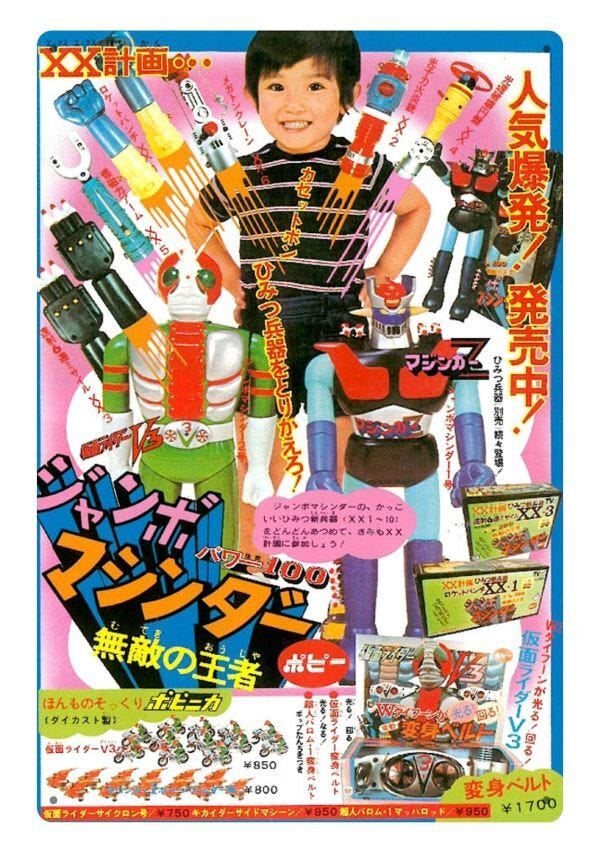

Sure, I’m biased. This photo of me ran in the September issue of Figure Oh (“Figure King”) magazine, anchoring an interview about Bandai’s re-launch of the“Jumbo Machinder” series of giant-sized robot toys, which debuted in 1973, and the re-release of one of its bestsellers, the titular hero of the 1975 UFO Robo Grandizer. At left, a now fifty year old (sigh) vintage original; at right, the upcoming new version. Sandwiched in the middle, of course, sits another fiftysomething original grinning at the camera.

They called me in because they knew I was crazy about toys. (And also, I suspect, because Patrick Macias and I used to write a monthly column for them.) I leapt at the chance, because UFO Robo Grandizer was more than a cool robot; the show, translated into Spanish, French, and Italian, among other languages, gripped European kids in a way no cartoon had before. It, and the accompanying tsunami of merchandise that hit foreign toy store shelves, were foreshocks of the Japanese franchises that would transform global tastes in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Japanese toys changed the direction of my life. Really! I would not be living here without them. I wasn’t lucky enough to get a Grandizer as a kid; it wasn’t sold in the States. But I did get one of his comrades. One of the first presents I recall ever getting was a giant red robot produced for the anime series Getta Robo G in Japan, and sold in the US as a “Shogun Warrior.” Back in 1978, a mixture of broadcast restrictions and cultural insularity kept the vast majority of Japanese cartoons off the airwaves. In those days, American anime fandom wasn’t a subculture so much as a secret society. (How times change in (double sigh) fifty years, where the medium is supposedly more popular among Zillenials than the NFL.) That robot sparked something deep inside me: the idea that somewhere far away could be found a people who took robots as seriously as I did. The hunt was on. I never really stopped.

I was very fortunate that my high school in the suburbs of Maryland just so happened to offer one of America’s very first Japanese-language courses. I was surrounded by kids who studied Japanese because it was the smart thing to do, in that Eighties fever-dream when it seemed Japan would rule the world. I didn’t care if Japan ruled the world or not. I just wanted more toys. On my first visit to the country, an Easter break homestay in 1989 or so, I snuck away from a guided tour to Asakusa and spent the entire time in the toy shops of the Nakamise shopping arcade instead. It would be decades before I ever set foot in Senso-ji, the resplendent temple that was our ostensible destination.

I could, and at some point probably should, write a history of Japan in toys one of these days. It would be my history, too.

I wasn’t anywhere near the first person to notice Japan’s toys. The first foreign visitors to arrive in Japan, after its ports opened in the mid-19th century, noted the gusto with which Japanese played. “We frequently see full-grown and able-bodied natives indulging in amusements which the men of the West lay aside with their pinafores, or when their curls are cut,” wrote the American educator William Elliot Griffis. “We do not know of any other country in the world in which there are so many toy-shops, or so many fairs for the sale of things which delight children,” he marveled in 1877.

Toy exports played a key role in jump-starting Japan’s economy in the Meiji era. By the turn of the 20th century, they had evolved from their folk origins into exquisite — and occasionally politicized — playthings. This one, made of tin and celluloid, portrays General Nogi leading his Russian counterpart to surrender negotiations after the Russo-Japanese War. Then as now, the toys adults produced often said more about them than it did the kids for which they were ostensibly made.

As Germany became embroiled in World War I and shifted its factories to wartime production, Japanese toymakers leapt in to fill the gap. “Looking through the Christmas stock at the department stores,” wrote The Star and Sentinel in 1916, “one is impressed by the presence of Japanese goods in unusual quantities, especially in fancy goods and toys.” By 1934, US toy companies were petitioning their government for tariffs to help stem the “invasion of the American market by Japanese toys” — a precursor of trade wars to come.

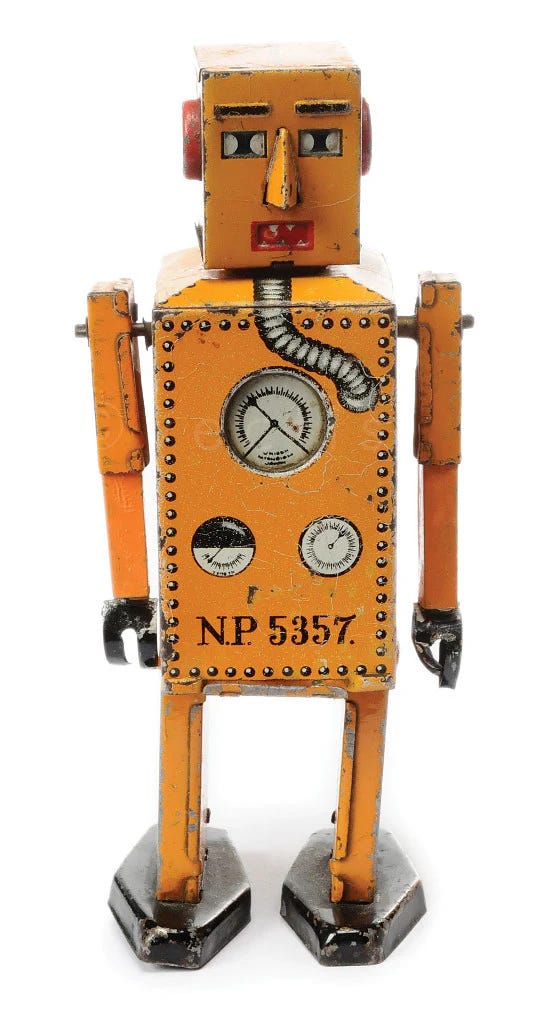

It might not surprise you to learn that world’s first robot toy was dreamed up by a Japanese toymaker. But it probably will surprise you to hear where it was made: China, or more precisely the Japanese puppet-state of Machukuo, in the late 1930s. In this charming little wind-up “Liliput Robot,” made by Chinese laborers to Japanese specifications for export markets, we see an early example of globalization — and trace the edges of Japan’s malignant Imperial ambitions.

During World War II, the government compelled toymakers to stop producing toys and convert their workshops into factories for churning out necessities for the war machine. This did not go unnoticed by the Americans. Military planners specifically targeted the areas of the city where toymakers clustered, such as Taito-ku and Sumida-ku, for firebombing raids. “It made a lot of sense to kill skilled workers by burning whole areas,” blandly remarked an Air Force colonel in a postwar interview that reminds one why Curtis LeMay quipped “if we lose, we’ll be tried as war criminals.”

Toys then jump-started Japan’s shattered economy. Within just months of war’s end, toys began rolling off of makeshift production lines, first in Kyoto, then in other major cities. Many were effigies of American military might: Jeeps hammered out of scavenged tin cans, cars and tanks, and later, B-29 bombers, assembled and painted in the very same neighborhoods that had been bombed by them just a few years earlier. None of this was compelled by the Americans; rather, it emerged organically, out of economic imperative, for Japan had been laid low and toys were among the only products they could produce quickly. They were also among first products the occupation forces green-lit for export after the war. The company Yonezawa sold more than a million tin B-29s to American buyers.

One can also chart the rise of Japan as an economic superpower in toys. Cheap tin playthings and vinyl dolls predominated until the Seventies. By that time Japan emerged as the planet’s second largest economy. This is where I enter the picture, being the recipient of one of those Jumbo-sized toys. Both the series, and me, arrived in the world in 1973. That’s pretty much me in the ad below, rocking the Seventies stripes and dreaming about the many and varied ways robots might wreak havoc on other robots. By this point Japan had more than recovered from WWII — it was feeling downright wealthy. And this manifested in all sorts of ways, including the increasing imaginative opulence of the playthings they bestowed upon their children.

The two characters shown here, Kamen Rider at left and Mazinger Z at right, are interesting in another respect: they’re characters that debuted on television and manga, respectively, making them early representatives of Japan’s rapidly growing fantasy-industrial complex.

Even here we see politics creeping into the mix, albeit indirectly. These “Jumbo Machinders” were roughly two feet tall and molded out of a sturdy plastic called polyethylene. OPEC’s boycott of any nations that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War sent the world into the 1973 oil crisis, sending the prices of petroleum products skyrocketing.

Grendizer (here flanked by his predecessors Mazinger Z and Great Mazinger, all designed by the manga legend Go Nagai) arrived in 1975. It aired in France the following year, sparking a boom that quickly spread across Europe. That boom was fueled by one Haim Saban, an Israeli concert promoter who lost his fortune when all of his shows were cancelled by the Yom Kippur war. He emigrated to France with one of his youngest stars, where he produced the recording of Grandizer’s French-language theme song. The record went platinum, making Saban a new fortune. Grendizer became a hit in many French-speaking territories, including in the Arab world. Saban used this new capital to continue purchasing the rights to Japanese shows — and create new ones of his own. But we’re getting ahead of the story.

The Iranian revolution caused a second oil crisis in 1979, forcing the world to reconsider its use of petroleum products — Japanese toymakers included. The giant-sized Jumbos weren’t just expensive to make; they were difficult to ship and took up vast quantities of space on the shelves of tiny Japanese toy stores. As such toys began getting more compact — and getting more complex.

The very first toy produced after war’s end had been a tin Jeep, the brainchild of Matsuzo Kosuge, whose story anchors the first chapter of the book Pure Invention. It was created from tin scavenged from American military bases, hammered into shape on wooden forms in a dilapidated barn. It was one of the first manufactured products of any kind to go on sale in late 1945, and Jeeps would remain a staple Japanese toy for many decades to come. Kosuge passed away in 1971, but I wish he’d lived long enough to see this:

By the Eighties, thanks to the advent of precision engineering and molding technologies, now cars could turn, origami-like, into robots. Transforming cars (and planes, and all sorts of things) flooded into global kids’ spaces right alongside the real-life cars roiling grown-ups’ markets. But even bigger changes were to come. To understand how big, you need to understand that we were in the middle of a trade war so fierce it was known as Japan Bashing. American politicians on both sides of the aisle portrayed Japan as an enemy. In April of 1987, President Ronald Reagan imposed a 100 percent tariff on Japanese semiconductor imports. The idea was to protect the American computer industry.

There was just one problem: he forgot to include toys.

A practically unknown toymaker named Nintendo released the Family Computer, aka Famicom, in 1983 in Japan. “It started with a phone call in 1981,” the creator of the device, Masayuki Uemura, told me. Nintendo “President Yamauchi told me to make a video game system, one that could play games on cartridges. He always liked to call me after he’d had a few drinks, so I didn’t think much of it. I just said, ‘Sure thing, boss,’ and hung up. It wasn’t until the next morning when he came up to me, sober, and said, ‘That thing we talked about—you’re on it?’ that it hit me: He was serious.”

Serious indeed. The Famicom, released in the USA two years later as the Nintendo Entertainment System, upended the idea of what it meant to play. Japanese didn’t invent video games, but they arguably perfected them, as a new class of heroes like Mario and Zelda won hearts and minds of children (and more than a few adults) around the globe, heralding a new era of virtualized play. Not to mention a “console war” in which Japanese companies like NEC, Sega, and later Sony fought for global mindshare, a battle Western gamemakers all but sat out for the duration.

Midway through the console wars in 1993 came an unexpected contender: Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. It was based upon a Japanese series called Zyuranger, created by a Japanese company with the intent of selling toys to Japanese children. But an Israeli entrpreneur by the name of Haim Saban — remember him? — repackaged it in a new format for American audiences, sparking yet another boom that has, in many respects, never really ended. Power Rangers, with its glorious spandex suits and the use of giant robots to solve problems, made me wish I was ten years old instead of an (ostensibly) adult twenty when it arrived. I’ve never actually watched an entire episode, yet even as a late middle-aged man dream of using giant robots to solve all of my problems, too. Bandai made a fortune selling “Megazord” robots and Ranger figures to kids from the show, bringing a distinctively Japanese sensibility to the childhood fantasyscape.

Japan’s “Bubble economy” popped in 1990, a few years before the Rangers arrived. But even as Japan should have been getting less and less relevant, an even more influential toy line arrived at the cusp of the 21st century.

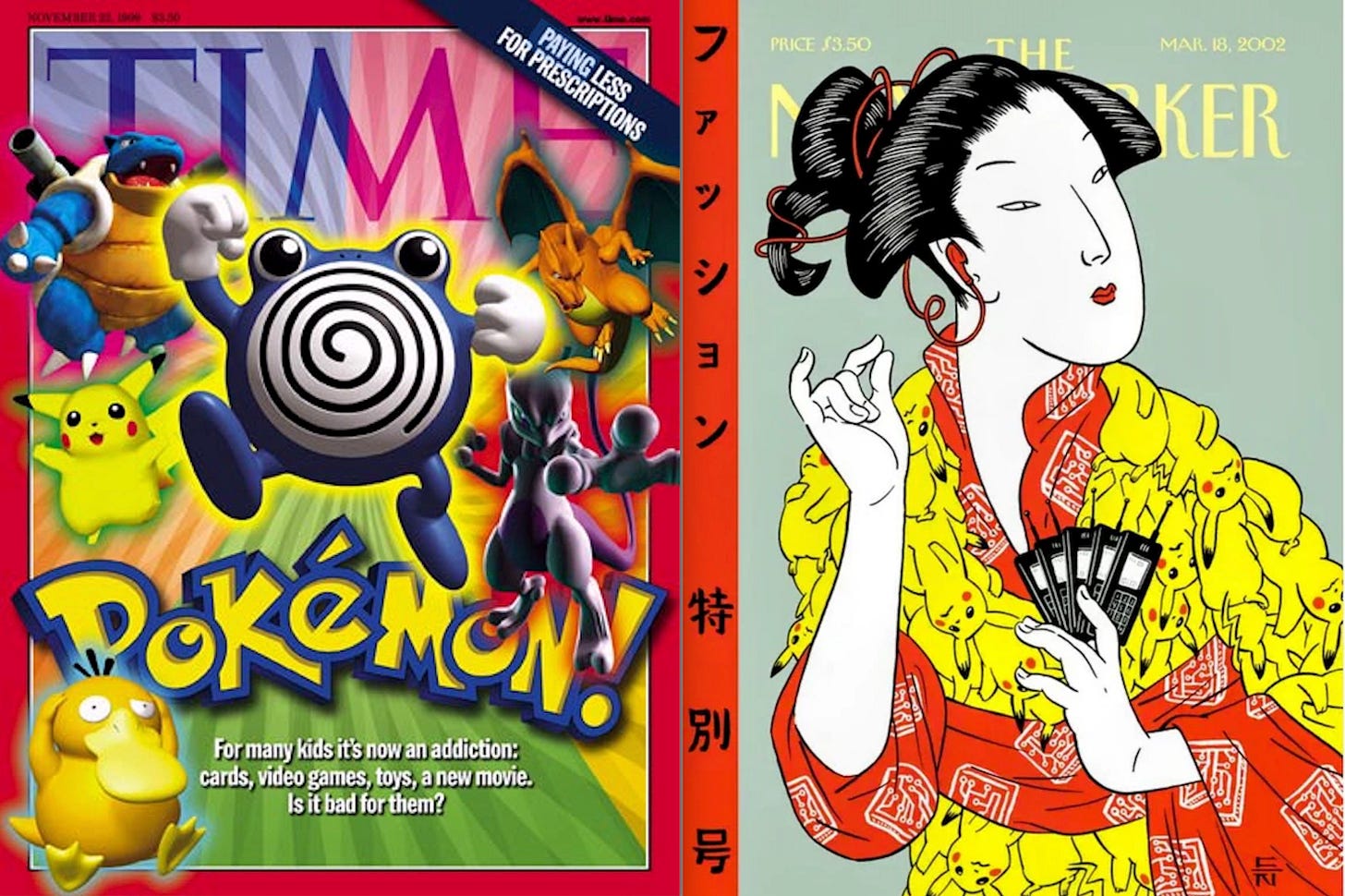

Pokémon dropped in Japan in 1996. Nintendo had small hopes for the game, originally. “I was told this kind of thing would never appeal to American audiences,” recalls Nintendo legend Shigeru Miyamoto of its development. Yet the corporate pundits were wrong. Pokémon Red Version and Pokémon Blue Version spread from schoolyard to schoolyard in Japan, surprising Nintendo, who quickly produced a card game and anime to promote the surprisingly popular title. When the trio arrived on American shores in September of 1998, they swept the nation like a virus. Time called it a “pestilential Ponzi scheme”; The New Yorker dedicated multiple covers to the franchise. This was more than a fad — it was a global phenomenon. Christian groups protested it; Saudi Arabia issued a fatwa against it.

From shows like Transformers and Power Rangers, everyone knew Japanese toymakers were good at their jobs. That they had this kind of cultural clout was shocking — to Japanese and Americans both. Perhaps no other plaything transformed the way children dreamed than Pokémon — and it was a product of Japan, no different from the amusements that had shocked observers way back in 1877, a century and more earlier. It heralded an age where the traditional markers of a nation’s success would be superceded by the power of fantasy — and Japan, supposedly out of the game economically, was now inexplicably leading the pack culturally.

It was a sign of all sorts of weirdness to come. But that brings us to the turn of the 20th century. Anyone care to read the toy-history of the 21st?

I’m almost done reading Pure Invention, loved Hello, Please (as I’m fascinated by Japans love of mascots, as a character designer myself!). I’d love to see you write a book on toy culture! And gachapon! Thanks for all the amazing books and blog posts!

As a Pokémon-related Substacker, I appreciate this.