Gal Den of Earthly Delights

Juliana’s Tokyo closed 30 years ago this month, but in some ways, the party goes on

(In addition to the regular voice-over of the essay, I’ve uploaded a video of a “field trip” to the remains of Juliana’s Tokyo in Shibaura — check it out on my new YouTube channel!)

For three years beginning in the spring of 1991, a legendary discotheque ruled Tokyo’s night scene: Juliana’s Tokyo. Fueled by young women who rallied under the banner of gyaru — gals — its decadence paralleled the glitzy excesses of the economic Bubble. Its closing in August of 1994 heralded that era’s spiritual end. By turns just another luxe nightclub and something more, Juliana’s made waves in popular culture that can still be felt as ripples today, if you know where to look.

Tokyo has never lacked for nightlife, but for much of the immediate postwar era, its watering holes centered on the whims of a specific sort of customer: the salaryman. The white-collar workers who built the foundations of Japan’s economic miracle worked hard and played harder. An ecosystem of drinking establishments emerged to fulfill their needs and tastes. After work, salarymen would unburden themselves over a beer or ten at the local izakaya. Cabarets were high-end hotspots with live big-band music and dancing girls, just the thing for impressing visiting clients, and hopefully helping land that big sale. Hostess clubs were more intimate venues where you took clients when the conversation started to flag. (Today, cabarets and hostess clubs are pretty much the same thing, but this is how it was back then.) And then there were “snacks,” laid-back little bars, often run by retired hostesses, where you went to unwind on your own or with friends.

By the 1960s, as a postwar baby boom funneled increasing numbers of young adults into Japanese cities, the night scene began to evolve beyond the needs of the salarymen. A National Geographic team, sent to scout then-exotic Tokyo ahead of the Olympic Games in 1964, toured the sights with the help of a young female guide. “Reiko is what is known as a toranshista garu – transistor girl – one who, as the name suggests, is small, compact, and full of energy,” they wrote in a three part series called “Tokyo: The Peaceful Explosion.” Reiko was a hostess, and she educated the (male, of course) reporters about what the Japanese were calling the “leisure boom.”

In some senses, it never really ended. MUGEN opened in Akasaka four years later, in 1968. Described as a “psychedelic zone,” this pioneering go-go club quickly emerged as the city’s place to see and be seen. A Japanese media report described it as “a storm of hallucinations,” with black-lit neon walls and pulsing strobe lights illuminating scantily-clad dancers gyrating on raised platforms, to the sounds of a live rock band performing under a funhouse-mirrored ceiling. Patrons included Yukio Mishima, Tadanori Yokoo, Issey Miyake, and even more importantly, the producers of the Godzilla movies. Two years later, they would set the grooviest scenes of Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster in a simulacrum of the club. “I went there often myself,” recalled Keiko Mari, who sang the film’s iconic theme song, Save the Earth. Yes, click that link. Don’t worry, I’ll wait.

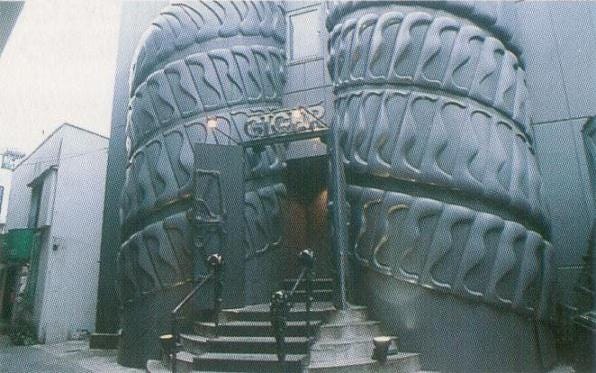

MUGEN set the literal and metaphorical stage for many an avante-garde dance club to come. Then, in 1978, the American film Saturday Night Fever opened in Japanese theaters, changing everything. Suddenly, psychedelia was out, and disco was in. Over the course of the Eighties, entire buildings in hotspots like Shinjuku and Roppongi filled with discotheques trying to one-up each other in terms of aesthetics and atmosphere. Maharaja, one of the first to institute a dress code, featured opulent gold furnishings and a marble dance floor. Turia’s sci-fi interior was designed by legendary “visual futurist” Syd Mead, of Blade Runner and Tron fame. And while it wasn’t a disco, a few stops away in Meguro was Giger Bar, with an interior designed entirely by Alien’s H.R. Giger, where I would drink my very first cocktail in 1990.

As Tokyo’s economy continued to grow and downtown discos grew more and more packed, club promoters cast about for locations with more space – and lower rents. Enter Shibaura, a patch of reclaimed land in Tokyo’s Minato Ward.

Shibaura is a series of artificial islands that were created in the 1910s by dredging out canals for fishing vessels and cargo ships to unload. In the prewar era it was home to many geisha “teahouses” overlooking the waterfront, serving up seafood fresh from the nearby docks. But when Tokyo relocated its cargo port further down the coastline in the Sixties, the neighborhood withered. By the 1980s, Shibaura was a quiet, even desolate place, filled with empty storefronts and warehouses. The combination of open spaces and cheap rents is precisely what attracted the creators of Juliana’s Tokyo.

Juliana’s Tokyo’s investors weren’t the first to discover Shibaura. A pioneer called GOLD opened in a converted warehouse there in 1989. But Juliana’s quickly eclipsed the competition in terms of pure, unadulterated decadence. It was a joint venture between a British leisure services firm and the trading company Nissho Iwai, who together poured a reported 1.5 billion yen into outfitting and staffing the operation. The resulting combination of dance music, glitz, glam, sex, and status spoke so much to the Bubble era that it felt like a physical manifestation of its times – or “The Nouveau Riche Bad Taste Festival,” as W. David Marx has called it.

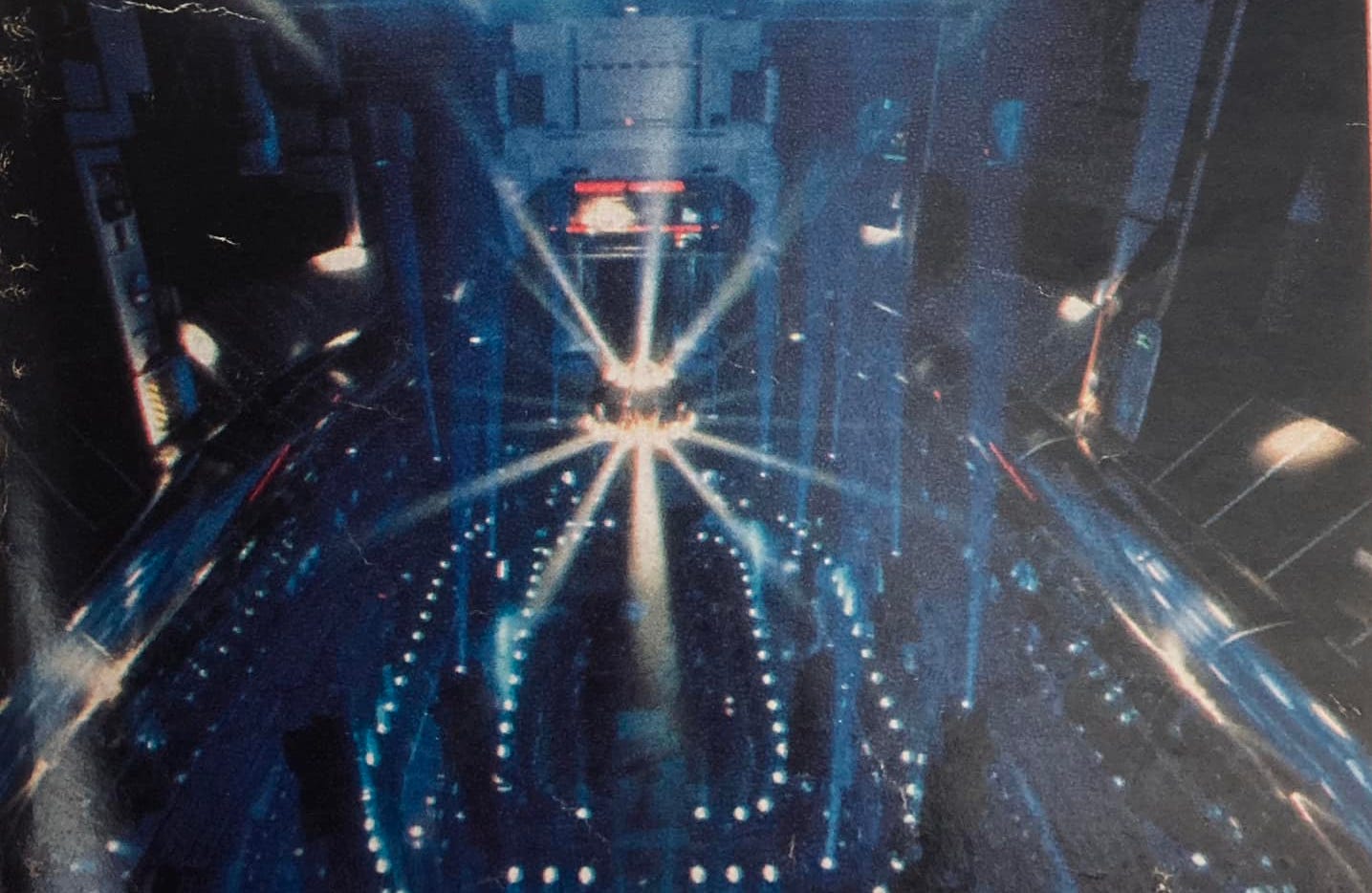

In the 2004 Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture, longtime Tokyo resident Mark Schilling described a night at Juliana’s thusly. “After being vetted by a tall, imposing foreign doorman for age, dress, and overall hipness, patrons walked through the large fractured-glass doors and past the official greeters — six Japanese women in glittering green minidresses, all bowing in unison — to a cavernous room that would have made a great setting for a high-life scene in a James Bond film. Underneath a huge chandelier imported from California, splashed by multicolored beams of laser light, bodies seethed to the Eurobeat produced by a twenty-six thousand watt sound system.”

That sound system was pumping out house and techno, and it represented the first time many Japanese heard these cutting-edge genres from abroad. Among them was one Yuzo Koshiro, music composer for video games, who injected a healthy dose of Juliana’s-inspired dance music into the soundtracks of bestselling games such as Sega’s Streets of Rage 2, which delivered them right back into the homes, and ears, of young people all over the world.

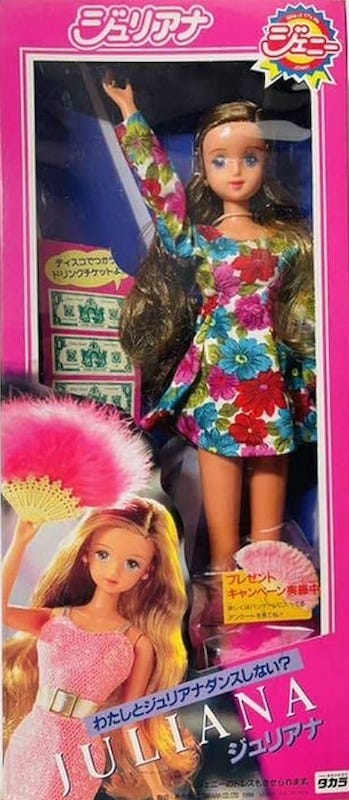

And those seething bodies? They belonged to “a new breed of woman” dubbed the gyaru, a Japanese approximation of the English word “gal.” If dance tracks were the heartbeat of Juliana’s, gyaru were its lifeblood. They were given preferential treatment at the door, access to VIP rooms, and most importantly, center stage on the dance floor, on special elevated platforms that let them whip the legions below into a veritable frenzy. (On the club’s biggest nights, more than two thousand people crammed within its walls.) Gyaru were generally college girls and office ladies. The idea of them shucking their sensible uniforms for skin-tight bodycon miniskirts and shaking their booties for besuited businessmen utterly enchanted the Japanese zeitgeist.

The way in which “Juliana’s girls” leapt from the shadows of Japan’s male-dominated culture to party on their own terms scandalized polite society. Critics portrayed gyaru as voracious man-eaters and contemptuous of men at the same time, never mind that the club’s owners were the ones really profiting off the displays of flesh. Even proponents couldn’t help but frame them in predatory terms. “If a gyaru were an animal, she’d be a cat,” wrote the journalist Kazuya Yamane in a 1991 book called Gyaru no Kozo (The Structure of the Gal). “Not a tanuki [Japan’s folkloric equivalent of the weasel], not a fox. Cats hide their claws behind cute faces and purrs, but possess the instincts to feed themselves.”

What really ground the critics’ gears, though, wasn’t eroticism or morality — it was independence. “They’re dancing like crazy and not paying attention to the men!” wailed the caption of one magazine feature. “The dancers, seemingly oblivious to the staring men… stare at their own reflections in the looking-glass walls,” remarked another observer. The raised platforms were women-only, making them a safe space in an environment where unwanted physical contact was undoubtedly common. “This is the only place we could have fun,” a 21 year old patron told The Washington Post in 1994, on the eve of the club’s shutting down. (That the closing of a Japanese disco warranted coverage in the Post goes to show you how much of a cultural mark it made.) “This was my place for making my stress melt away. Now where am I going to go?”

Juliana’s Tokyo closed in August of 1994. A disastrous 1993 magazine promotion featuring staged photos of almost naked dancers drew unwanted attention from the police, forcing the club’s management to institute a dress code and ban gyaru from the elevated platforms. As Tokyo’s party people sought out less uptight venues to melt their stress away, the club struggled to fill its dance floor. The costs of maintaining such excess, not to mention a growing chorus of noise complaints from Shibaura residents, played into the decision as well. But perhaps the biggest factor of all was the end of the Bubble era.

Economically, the Bubble popped in 1990; culturally, it popped a little after Juliana’s shut its doors in late August of 1994. Five months later in January 1995, the Great Hanshin Earthquake devastated the city of Kobe, and the nation watched in collective frustration as the government totally bungled the rescue efforts. Then came something even worse: Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system. Now the nation watched in collective horror as their leaders scrambled to deal with the madness.

More shocks followed. A disgruntled former police officer, later revealed to be an Aum cultist, attempted to assassinate the chief of the National Police Agency. A few months later another member hijacked a passenger jet, in a failed attempt to gain the release of the cult’s leader from custody. The epic fails of the disaster response and the ongoing terrorist attacks conspired to make Japanese wonder if anyone was really in control anymore. This is when the so-called “Lost Decades” really began.

Other clubs followed in Juliana’s footsteps, of course. But none captured the zeitgeist in the way Juliana’s had. The vibe, for lack of a better word, had changed. When Juliana’s opened in 1991, the future still seemed bright. After 1995, things felt downright bleak. In 1997 the Post, which just a few years earlier had evinced such an interest in Japanese happenings that it saw fit to cover Juliana’s closing, was gleefully declaring “GOODBYE, JAPAN INC.” on its op-ed page. Yet amid the depression and confusion and chaos of Japan’s socio-economic implosion, interesting things were happening down at street level. New subcultures and lifestyles emerged from the wreckage of the Japanese economic miracle.

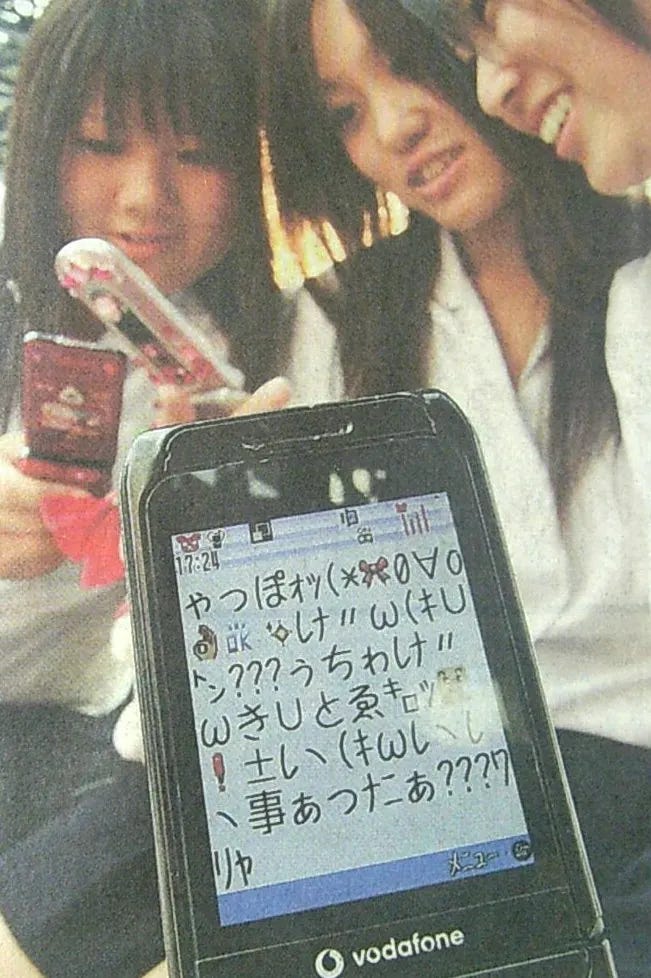

Their most enthusiastic innovators were called kogyaru – the evolution of the gyaru who had ruled the roost at Juliana’s Tokyo. Kogyaru, or “little gals,” dreamed of emulating their predecessors, but there wasn’t much to celebrate in late-Nineties Japan. Kogyaru also tended to skew younger: more high school, than collegiate or corporate. As a result these girls showed less interest in partying than in hanging out. Kogyaru repurposed all sorts of technologies into what one observer called “communication cosmetics,” re-envisioning Hello Kitty as an ironic symbol of girl power, texting on pocket pagers, building literal face-books of friends from “print club” sticker-photo booths, and “hacking” the font sets of cell phones to make emoji a new digital lingo. In 2000, an impressed William Gibson dubbed them “mobile girls,” a play off of the “modern girls” of the prewar era.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Japanese girls pioneered the basics of social media on the streets of Tokyo a decade before Silicon Valley techbros finally figured out how to commoditize it. Which makes it no exaggeration to say we’re all living in a world the kogyaru created. The end of Juliana’s Tokyo symbolized the end of Japan’s most decadent era, but it also heralded a new beginning — not only for Japan, but all of us. The gyaru walked so that the kogyaru could run, blazing a trail for the rest of humanity’s soon-to-be hyperconnected future.

This was a fun journey down memory lane. While my Japan tenure (and Tokyo area tenure) was when Juliana’s was still a going concern, I never did make a pilgrimage. Box not checked on the early 1990s expat bingo sheet 😆

This was interesting to read. My image of kogyaru is different— I felt the media treated them as outsiders with long dyed blonde hair that were not to be taken seriously.